Administration College students

Students gather outside the Administrative College in Port Moresby during the early 1960s. The College became a meeting ground for young Papua New Guineans from across the Territory, a place where classroom lessons turned into late-night discussions about equality, justice, and the possibility of self-government

Oala Oala-Rarua on Responsibility ABC video interview

Description

By the mid-1960s, Oala Oala-Rarua had already emerged as one of Papua New Guinea’s most capable public servants and a likely future leader. A former teacher who had travelled widely overseas, he saw independence not simply as a political slogan but as a profound responsibility. In his words, independence meant “a great responsibility being passed from Australian hands into the Papua New Guineans.” His view captured both the optimism and the weight of expectation felt by the emerging nationalist generation—that self-government was not just about freedom, but about proving themselves capable of running the country’s affairs [1].

Reporter

It's here that Oala Oala Rarua, has his campaign headquarters. Oala is a former teacher and is now one of the highest ranking Papuan public servants. He's travelled widely throughout the world and is one of his country's obvious future leaders.

Have you found much interest in independence among the people you've spoken?

Oala Oala-Rarua

Oh yes, very much, very much.

Reporter

What exactly does independence mean to you?

Oala Oala-Rarua

I think independence will mean to, or well it will mean to me personally, means a great responsibility being passed from Australians hand into the Papuans and New Guineans.

Tos Barnett Speaking on Independence, Law, and the Administrative College

Source: Audio courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Tos Barnett interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2010, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/39.

Description

Tos Barnett was an Australian lecturer who encouraged debate and critical thinking, inspiring his students to question colonial authority and imagine self-government.

This interview recalls how East Africa’s independence experience offered a model for what Papua New Guinea might achieve. Inspired by Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, Toss Barrett and colleagues like Peter Lawler and David Chenoweth began pushing for a localised court system and the training of Papua New Guinean magistrates. Working through the new Administrative College, they used letters, lobbying, and creative partnerships with figures like Dr Gunther to advance reform—even when “independence” itself was still treated as a forbidden word in official circles.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes, going to your six months in East Africa.

Tos Barnett

That's right. We went to East Africa.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes.

Tos Barnett

And what I really gained from that as well as factual information and practical hints was what it would be like in Papua New Guinea after independence.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes.

Tos Barnett

Because both Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania had recently, over the last few years, been progressively gaining independence and their institutions were working. The British colonialists had withdrawn or were withdrawing and were just there on an advisory basis. The Africans were really doing their own thing, and they looked as though they were doing their own thing. And they stood straight with their physique, and they were very positive in their thinking. And they seemed to be coping, and it gave me a confidence that we could run a court system which included a lower level of court run by Papua New Guinea magistrates, and it would be much better than the prison system in evening. And so I returned to Port Moresby all fired up to do that. And there was a small group of senior people with the same idea that I was able to cooperate with. It was Peter Lalor, who was not only the public solicitor, but he was also chairman, or president rather, of the Papua New Guinean Law Society. And in that capacity, he was able to write letters to Dr. Gunther as acting administrator, requesting consideration be given to a magistrate training course. And Gunther was also the interim chairman of the two yet to be formed administrative colleges. So in that capacity, so he had two roles, one as the head of the administration and the other was chairman of the college. The principal just appointed to the college was David Chenoweth, who was absolutely overflowing with enthusiasm to get the Papua New Guinea administration localised. And all these people had a vision that independence was just around the corner even though this was being denied by Mr Charles Barnes who was the Minister for Territories in Australia and by senior administration people it was almost a dirty word to use the word independence, so in fact what we did was, we formed a close group, and I as under Peter Lalor's leadership, would write letters on his behalf, from the President of the Papua New Guinea Society Lawyers' Society, to Dr. Gunther. And I used to draft Dr. Gunther's reply, and we'd copy the letter to Chenoweth, the principal of the college, and I'd help him with the administrative worker getting his reply. So we set up a seemingly working relationship, which was, well, it was working, but we were all in the know, and it became a very powerful lobby group.

The Minister for External Territories was just not interested in the idea. At that stage, as far as I could see, he was not interested in there ever being local Papua New Guinea magistrates. He was prepared to countenance us having a training course for assistant magistrates. We wrote letters also to the Chief Justice of Papua New Guinea, Sir Alan Mann. He might regret I haven't spoken about my, in the section, and one day I'll go back and get to find out. A very interesting man but he was not bowled over with the idea of having Papua New Guinea magistrates, he was prepared to contemplate it, but he certainly insisted that the training should be of a very high standard, much higher than what I had seen in East African countries. He wanted them to have solid knowledge of ethics and the principles of law and procedures of courts and basically be a junior version of his Supreme Court, I think. But we did get everybody on side. The administrative college was anyway proceeding to be formed and it included management training courses for middle-level and senior-level public servants, and they wanted law lectures included in that. I asked to be appointed to the position of Senior Lecturer in Law there and sought the Secretary for Law's approval to make that transfer. He wasn't supporting the new initiatives, but he did not want me to be assistant secretary executive in his department and I had the seniority to claim that position. So he released me and Jenny, and I moved to the administrative college in probably 1966, '67.

Jonathan Ritchie

Right. So had the college been operating by this time?

Tos Barnett

It wasn't operating.

Jonathan Ritchie

Oh, okay, right.

Tos Barnett

It was still the Public Service Institute.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes.

Tos Barnett

A really low-level training institute in Konebodu.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes.

Tos Barnett

But the grand design was to have a big college, residential, with important teachers and a high level of intellectual capability there. A college of excellence really and Chenoweth really believed that was possible and so did Lalor and so did Gunther and I wanted to be part of that. The staff houses, some of the staff houses had been built and Jenny and I moved into and lived in one of the staff houses and I set about preparing the scheme for a local court system run by Papua New Guineans and the syllabus for the training and the principles for their recruitment and

Tos Barnett on University Life and Student Politics

Source: Audio courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Tos Barnett interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2010, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/39.

Source: Image courtesy of the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery, Port Moresby

Description

In this section Barnett contrasts his teaching experiences at the Administrative College and the newly formed University of Papua New Guinea. While Administrative College students were career-focused public servants, university students were more varied—some highly motivated, others adrift. He recalls teaching future leaders like Tengen Sigoaru and Arnold Amet, and witnessing John Gunther’s firm but pragmatic handling of student activism. These were years of intellectual ferment: Ken Inglis was shaping a national history curriculum, and the lines between Administrative College and the University were porous, producing both tension and excitement in the lead-up to independence.

Tos Barnett

… it quite happily I never completed my PhD but I never regretted not completing it. Yes, I went to the University and seen a lecturer in law. I was impressed by the difference in the, in the motivation, of the students. I mean at the ADCOL [Administrative College] they were older people they were trying to get practically get their career in gear and move on, they knew just what they were going to be doing. And the university students were university students, like everywhere. And some knew why they were there, some didn't, some were studying, some were not. But my students included Tony Siaguru, …, who became a judge. Bernard Sakora, Mari Kapi, is it? The President Chief Justice, or he was until a few days ago. Maybe he still is. Arnold Lambert was in the next class coming up. Truly wonderful people with enormous intellects and integrity. I remember Siaguru could do anything, you know, he had all the intellect, all the ability, all the charm, but little of the motivation at that stage. I recall attending a staff meeting when the results were going to be discussed. And if he hadn't got his exercise in, his last assignment, I'd tried it, but I couldn't persuade nobody he was going to be failed if yet again his assignment was not in. And it hadn't come in. We were all around the table and I could see Siaguru's name was coming up and I asked to be excused. And I went outside and I ran to my cubby hole and there it was, his assignment. I. …

Jonathan Ritchie

Quickly marked it!

Tos Barnett

I hadn't read it, but I brought it in. He was so close to failing. And I actually did fail Somare in law. He got through on supplementary examinations, but I've always remembered that I failed the Prime Minister in law studies. Yes.

Jonathan Ritchie

He probably hasn't forgotten either. Was Ebia Olewale, was he studying, did he do law?

Tos Barnett

No.

Jonathan Ritchie

Okay.

Tos Barnett

No, I don't think he, was he at ADCOL?.

Jonathan Ritchie

No, he wasn't. He was a teacher's college, but I think he may have gone to UPNG for a year or two, but not perhaps until a bit later, early 70s.

Tos Barnett

No, I didn't know him until I moved away from the constitutional area.

Jonathan Ritchie

Right, sure. Yes.

Tos Barnett

But in the meantime, Chenoweth had left the ADCOL, and a fellow called Jerry [Gerald] Uncles was appointed. He was sent to be a Canberra bureaucrat, and he had a totally different approach. He wanted the name College removed and restore the name Training Institute. He wanted to, and did, put a fence up between the administrative college and the university so that it discouraged fraternization. Because he thought that the students were demoralising the public servants, he was very different. And I think from then on, the administrative college started to sort of go down and become a plebeian sort of institute.

Jonathan Ritchie

Its role was taken over a bit by the university.

Tos Barnett

They were exciting days when the two institutions were basically sharing the same premises. I think that really helped the administrative college too.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes.

Tos Barnett

I remember attending in the administrative college lecture hall lectures that Ken Inglis was giving in history to the university students. And he was consciously creating a part of New Guinea history or feeling for a history for Papua New Guineans and looking at things through their eyes, the colonisation. It was very exciting, very, very moving. Yeah.

Jonathan Ritchie

Do you want to take a break for the one?

Tos Barnett

Yeah, we've got yeah, at the University, one of my memories was visiting John Gunther, who at that stage was still the, I think he was still the Vice Chancellor of the University. John Kaputin from the Trobriands was leading student protests and had walked into Gunther's office and sat himself in there and said he was taking over the office. And I remember Gunther walking in, he was quite a big man. John was quite a small person and Gunther said, “Hey you!” and picked him up and put him out. But he was a good choice first. …

“The Administrative College was supposed to teach administration, but what it produced were politicians” — Retrospective oral history

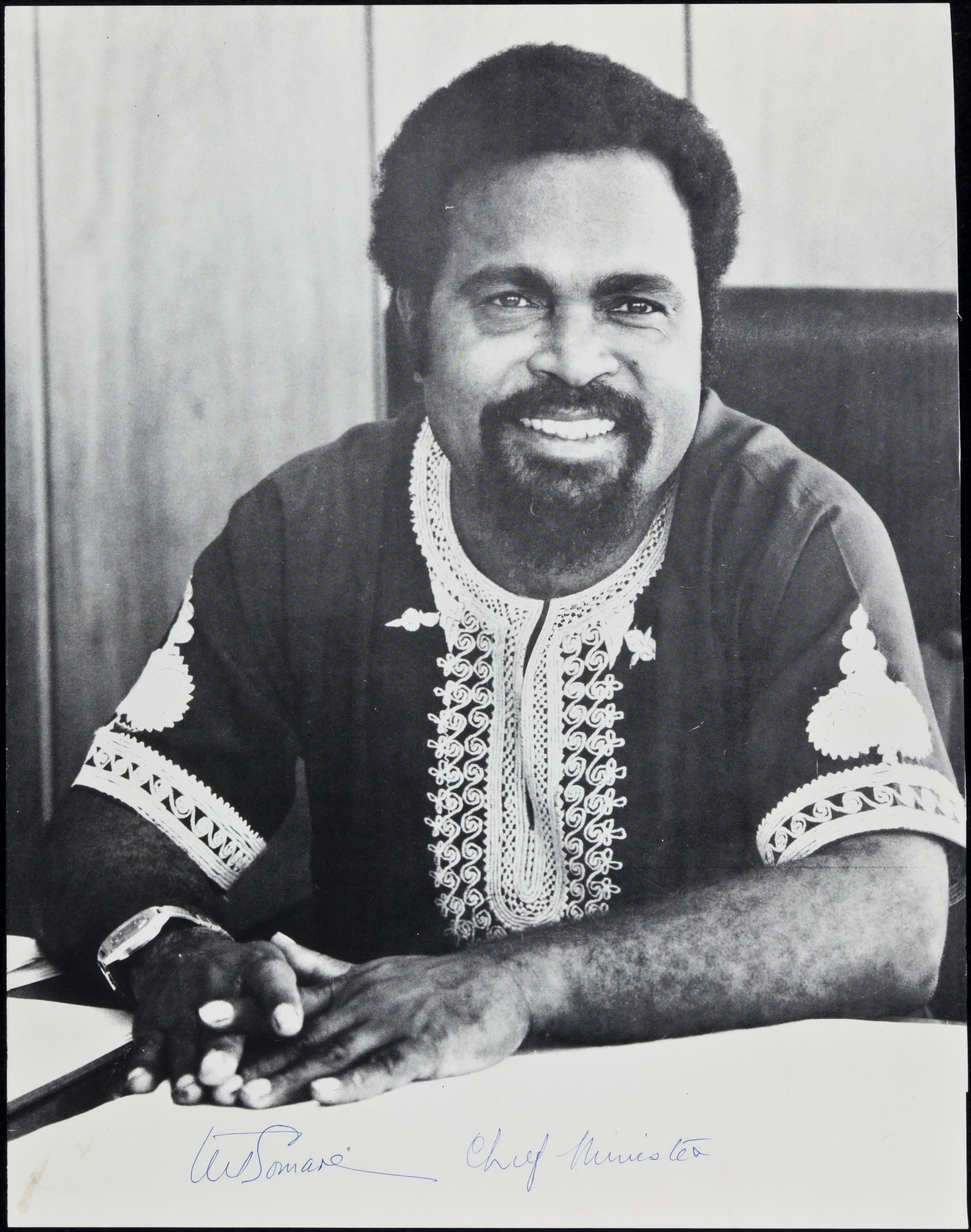

Michael Somare on Early Inspirations and the Legislative Council

Source: Audio and image courtesy of PNG Speaks and the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery

Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare inspired a generation. As a student and young leader, he helped turn friendship and debate into nationhood.

Description

Somare recalls how his first political consciousness emerged in the early 1960s, shaped by teaching Australian and British history and by encounters with radical figures like Sir Peter Lus. His fluency in English brought him into the Legislative Council as an interpreter, where he translated debates between Australian officials and Papua New Guinean representatives into Pidgin. Sitting in the chamber and listening to the exchanges sparked his interest in politics. These experiences, combined with the Legislative Council elections of 1964 and the presence of nominated members, gave Somare an early sense that Papua New Guineans could—and would—shape their own political future. What began as interpreting soon became active engagement, laying the groundwork for his eventual role as PNG’s leading independence figure.

Ian Kemish

Thank you. This is an interview with Grand Chief Sir Michael Somari for Papua New Guinea Speaks. It's a great honour to begin this project by talking to Sir Michael. Just on this point, on this point about the history of Australian colonialism, you have all that background You know, you're born in the forties, not that long after the period...

Michael Somare

No, not long after the...

Ian Kemish

And, you know, we were talking yesterday about the foot report and all this kind of thing. I mean, this is the question I wanted to ask you. When did it come into your mind that Papua New Guinea should be an independent country?

Michael Somare

Well, it came to my mind in nineteen... '60s, I think we were involved in. Or they were giving us, teaching us geography of Australia, Australian six states, how the Australians, British move in and start bringing the unwanted the British by a loaf of bread, stealing a loaf of bread. something like that, punishment, you have to be deported somewhere to the new colony. And history like that, you know, and I thought, you know, that's something very interesting. Then of course, when I started teaching, our history was Australian history. I did Australian history and studied, you know, and all these things are mentioned in the books about them. (Ian Kemish: “Yeah, right”). I also did the British history. We read for my matriculation. We had to read all these books. I remember these things very well. My thought of becoming politics is it was inspired by Sir Peter Lus, now Sir Peter Lus, but Peter Lus at the time, the rascal, the radical, and he came to my house in Hohola, Silkwood Street. We had these little dog boxes, I called them. And we were put in this, you see, for us, the public servants. I was fortunate to have enough education so I could be put in Ranuguri [Housing Estate]. But when I got married to Veronica, when I started working as a teacher, I taught in the schools where we were provided our own accommodation. And when I decided to become a member of parliament, I ran for Sepik electorate, or East Sepik electorate, they call it. That's both Madang, Manus, I'm sorry, Wewak, East Sepik and Madang. That's first, in 1964, that’s when the legislative council was introduced, and they thought that they [would] divide the country that way, so my mind in politics. I just want say came in about 60s and 70s I was interested in because, I think, one thing the Australian, I must thank Australian administration at the time, they were looking for English speaking people and I happened to be, you know, a little bit fluent in English and I thought, you know, they could use me to interpret. Me and the five others two from Papua, two from New Guinea Islands, and myself from New Guinea mainland, and one another, one of the other, of course, an Australian. He's here, he's around here, Brian Howe. He was a district patrol officer in Wewak, and when I became Chief Minister, then he left to come back to Moresby and work in Moresby. There were quite a few of us so I thought I was interested. Then through the legislative council I was interested in politics because I was interpreting and I thought it must be very interesting. So I saw the first nominated members, I interpreted for them. Simultaneous translation and, we only have simultaneous translation in the council, as they speak English. You, at the same time, understanding English, you have to translate it into Pidgin and so. And that's the first [time] that got me interested and I saw Peter Lus and saw the old fellas start talking and I thought, yeah, it must be interesting and it gave me, you know. Yeah. Not realising later on that I was going to end up being an a politician.

Jonathan Ritchie

So are you sitting, you're actually sitting in the Legislative Council Chamber.

Michael Somare

Yes, we have some translation system. Our Hansard was produced by the Australians because they have to... we didn't have Papua New Guineans. And they got the Hansard out as soon as they finish, they go, someone else come in and quite a number of them were employed there. So they're listening to people like these ideas. Yeah, Well, he spoke in Pidgin at the same time, we're in the box, interpreter's box, translating his Pidgin into English.

Ian Kemish

What did the proceedings look like? What was the interaction like between the people?

Michael Somare

Members of the House of Assembly. Well, we had a lot more official members. Australian government decided to camp the first House of Assembly with the all official members, former district, all district commissioners and all the secretaries of departments and your Your dad [Jonathan Ritchie] was one of them.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yeah, it was later.

Michael Somare

That's right.

Jonathan Ritchie

Not in the first house.

Michael Somare

Not in the first house, but later on. That's right. It's a similar.

Jonathan Ritchie

That's right.

Michael Somare

After the first house, second house, then when your dad was there, yeah. And you had some of, they just say some of the others.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yeah, yeah.

Michael Somare

So that's how I got quick interest in politics. Stuck by it, you know.

Jonathan Ritchie

Were you also aware of what was going on like in Africa or in Africa?

Brian Jinks on ADCOL Training and Australia’s “Wrong-Headed” Policies

Source: Courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Brian Jinks interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2008, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/12.

Description

Jinks describes how the Administrative College, despite being designed to train Papua New Guineans for senior public service, struggled with outdated curricula and teachers who had little knowledge of the country. While some students excelled, many grappled with English, which he saw as the central barrier to advancement. He criticises Australia’s broader policy failures: restrictive education pathways, resistance to sending Papua New Guineans to elite schools, and misplaced hopes that PNG might become a “settler state.” Even the later Senior Executive Program (or “Septics,” as he called it) leaned heavily on management jargon rather than practical learning. Jinks argued instead for hands-on training, mentoring, and secondments in Australian organisations to prepare Papua New Guineans for real leadership.

Brian Jinks

There were people who've been a pinch hunt.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes, I was thinking that, yeah.

Brian Jinks

A number of them, and then there were others, I can't remember.

Jonathan Ritchie

But mainly Papua New Guinea.

Brian Jinks

All Papua New Guinea, yes. The administrative college catered almost exclusively, catered entirely for Papua New Guineans, apart from the induction courses that were run for a while for cadet patrol officers in the mid-60s, mid and later 60s. And those courses were no better than them. Not really. But other than that, it was all Papua New Guineans. And they started off with essentially an equivalent to the intermediate certificate and an equivalent to the leaving certificate, which were called stage one and two or something or another. And then '66 must have been the first year of what was called the Diploma of Administration, which was a two-year course. But it was just an academic course, basically with politics, public administration, history style of subjects, and a bit of anthropology thrown in. And it was really, no, it wasn't of any real... I mean, it was of intellectual use, I suppose. But the content was, you know, the people who taught it, I'd been in Papua New Guinea. All the others, I think, were imports. The anthropologist was a young guy who'd been in Singapore. He wasn't a Chinese ethnic, but the law lecturer was an ex-professor from the Dutch East Indies, from Indonesia. He actually, he was a quite a notable person, Pieter Drost [editorial note: P. N. Drost — a Dutch international-law scholar known for the two-volume The Crime of State 1959], one of the “Drostes”, the chocolate family that spelt it differently. He was another branch of the family. He was an international, one of the first international experts on space law. But for a variety of reasons, which I... Pieter and Dot and Rhonda and I became quite good mates later on when he retired. He went to live in Dee Why in Sydney. But, you know, Peter knew nothing whatsoever. Most of the people couldn't understand him anyway because he had a fairly solid Dutch accent. The lecture in history was a bloke called Peter Biskup [editorial note: co-edited Readings in New Guinea History (Angus & Robertson, 1973) with Brian Jinks and Hank Nelson]. Again, a guy with a very colourful colorful, but I mean, you know, he'd been in Czechoslovakia during the year. He comes from a very wealthy and notable family. Very clued. I believe he's not very well now, Peter, as far as I know. But I mean, nobody had any background in Papua New Guinea.

Jonathan Ritchie

Apart from you.

Brian Jinks

Yeah, but then you see, I didn't know, what do you teach Papua New Guineans about becoming, what they were supposed to do was to become senior public servants? And from fairly early on, I think what I was saying, and possibly others, one of their major problems was English, facility in English. There were a few, such as Joe [probably Nombri], Bill Lawrence, did anyone run across Bill Lawrence? Philip Baraga, people like that. Some of them were very fluent, very good. But most of them really struggled. And it was a major, major, major problem all the time. And it was partly because of poor teaching and stupid curricula and all that sort of stuff, bad techniques and so on and so on when they were taught. And of course, some of them grew, you know, they didn't really have a lot of formal education, some of them. And really the thing was, I used to think, put them in the corner, not put them in the corner, but put them at the desk next to somebody and let them learn that way. It's networking and all that sort of stuff, just observation. That's the way, you know, to do it. But there wasn't a structure there. There wasn't, well, you know, you only have to read the history books to find out what wasn't available. And the people weren't willing to do it anyway. The senior officers weren't willing to have was the term. After the various bulls and kanakas and various things, then the racist expression became “orly”. (Jonathan Ritchie: “I haven't heard that, orly”). In pigdin, you know, orly ***. Oh, yes. You know, “orly”? And that was the demeaning, the derogatory way. When you could no longer say kanakas and bulls and so on, you used to say “orly”. Oh, “orly”. Anyway, they didn't want “orly” in the room. But then again, I mean, of course, it's part of the basic policy. I mean, all this business, this nonsense about no elites. It was deliberate, has luck, no elites, seventh state, you know, all this sort of garbage. And I think you find a lot of the people at that time certainly believed it. I ran across people who honestly believed that Papua New Guinea would probably become a seventh state of Australia, truly, in Papua New Guinea, and why it's, I mean, absolute nonsense. And then, you know, oh, we mustn't, we mustn't.

I can remember when the Trobriands, there was a lad there, he was the son of one of the medical orderlies at the hospital, Papua Medical Order, not a Trobriander, but anyway. That lad was at school, at a boarding school in Queensland. Very few, most of them were mixed race, but very few went to boarding school. And people, oh, you know, we... mustn't have elites, mustn't have a, you know, and that, I mean, that was the government's policy, it was in Australia's policy, has that policy in everything, you know? So when you get to independence and so on, where are your leaders? Well, they just, nobody's ever had a go at getting them out, you know? So it was just, oh, you know, the whole thing was just wrong-headed, and while towards the end of that period, they set up a thing called, I think it was called the Senior Executive Program. Yeah, it doesn't matter. And people who'd been through the administrative college and some of the early university graduates, probably, were put into this thing. And they were going to do all kinds of things. They were going to have management seminars and blah, blah, blah, blah. And I said, look, the guy in charge of that for quite a while was a bloke called Jack Baker. Jack Baker. Jack was a great mate of Graham Hoggs. In fact, they went into partnership in a caravan park on Bribie Island after they left PNG, but it didn't last all that long. Jack was, he was a kiap. He became inspector of something or another at the Public Service Commissioner's office. And he was the sort of that area in charge of this program. And I remember saying to him, “Look”, as I said before, “put them in the office and let them learn by looking and doing”. I mean, it's all you can do, and people denigrate it. There's plenty of grounds for denigrating it, but it's the best we can do at this stage. And we run all these management seminars and all that sort of stuff and blah, blah, blah.

Well, a lot of the stuff that they were going to teach, I mean, I think most management, having spent three years at the Graduate School of Management at Macquarie, my opinion is that most of this management instruction is absolute ******** but snake oil, make a lot of money out of it. But you know, whatever the latest jargon is and sell it to people. Anyway, the people we had doing that at the admin college were a bit better than that, but not a lot better. And they were getting other people in to do these sorts of programs. I said, look, send these guys down to organize parallel organizations in Australia, work out who's gonna take over what. Send them down to parallel organisations in Australia, let them work alongside those people for a while, learn a bit about it, and then put them coming back and put them in charge of the show back here. And then have the whites move over there and help them. And that's the way to do it. But of course, so none of that happened. What was I going to say, something or another? I can't. Senior Executive Program, that's right. “Septics”, what I used to call them. And I'm just going to drink water.

asdfsadfasdf

Recognition and Responsibility

The first classes at the Administrative College were small but ambitious. In 1964, Gavera Rea won the Neil Thompson Memorial Prize for general proficiency, while Albert Maori Kiki and John Kaputin were awarded the staff prize for citizenship.[2] Such accolades highlighted their promise. Reports praised the Student Representative Council (SRC) as “helpful and valuable at all times,” suggesting the Administration believed it had succeeded in nurturing loyal, civic-minded leaders.[3]

Ted Wolfers on Manuscripts, Independence, and Early ADCOL Life

Source: Courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Edward (Ted) Wolfers interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2009, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/33.

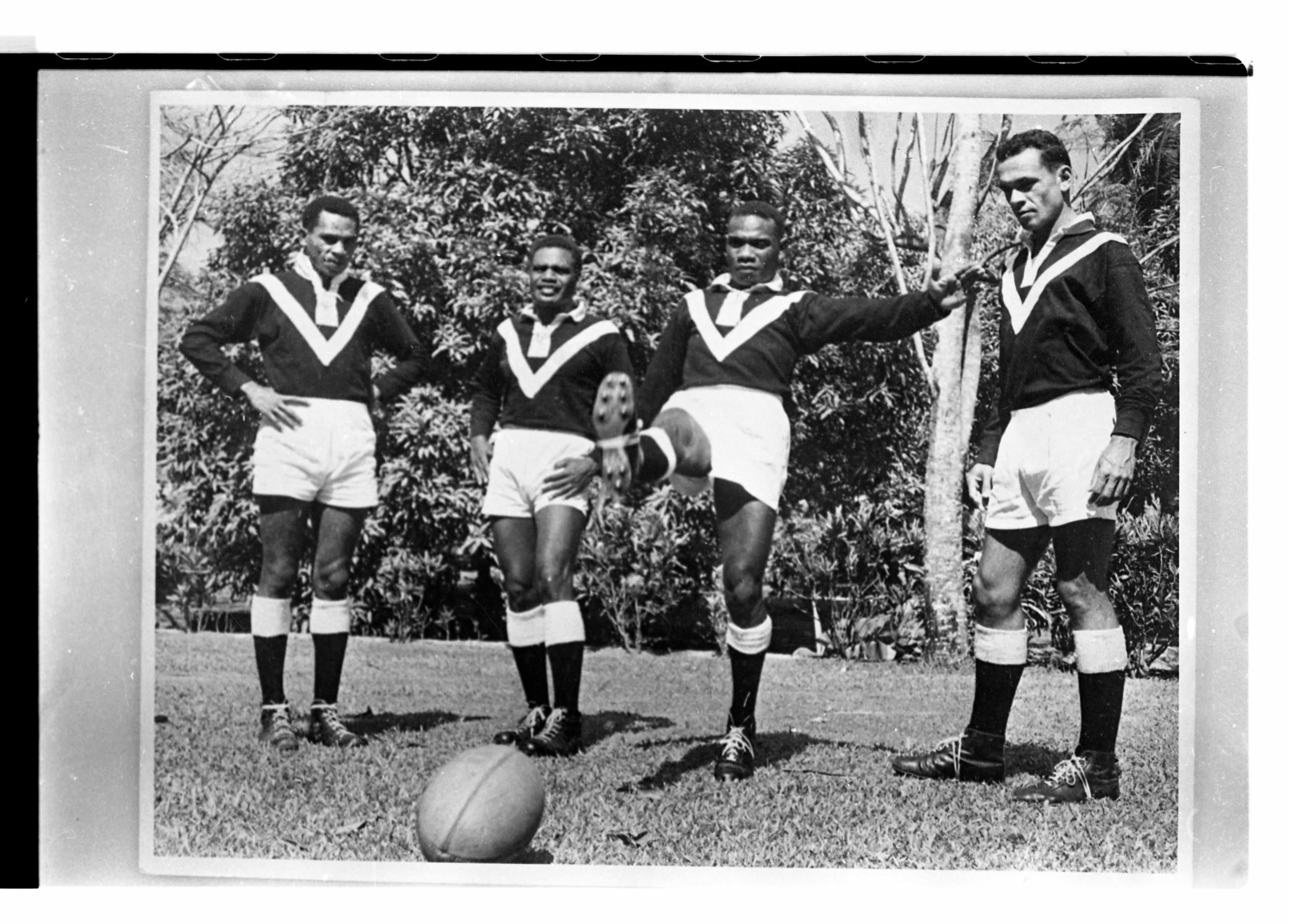

Students from the Administrative College play rugby in Port Moresby, early 1960s. As lecturer Ted Wolfers later recalled, sport was more than recreation — it built friendships and a sense of solidarity among young Papua New Guineans who would soon become leaders of the independence generation.

Image courtesy of PNG Speaks and the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery.

Description

Wolfers reflects on his efforts to encourage Papua New Guinean voices in print during the 1960s, pushing back against Australian assumptions that locals could not think for themselves. He carefully preserved original manuscripts and now plans to republish them under real names, correcting decades of misattribution. Independence, to him, always seemed inevitable—though the timing was uncertain—and his travels to Samoa offered inspiration from its participatory constitution. At the Administrative College, Wolfers experienced both suspicion and solidarity: suspicion from officials wary of his interest in public service pay disputes, but solidarity from students who came to see him as “brother”. Life at Six Mile was socially intense and formative, forging lifelong friendships that shaped the next generation of national leaders.

Jonathan Ritchie

… Michael under another name.

Ted Wolfers

Well, what's interesting is the Australian government's recently published its records of who they thought wrote what and those records are wrong in almost every case. But also because there was so much mistrust that Papua New Guineans were capable of thinking for themselves, the assumption was always that they were being manipulated. I made a point of always keeping the original manuscripts because I don't believe I manipulated people. I would encourage them to write I would show them the editing we were doing, which was often for grammar and spelling and so on, and some of those names have never been made public, possibly in some cases there's no great interest in it, but in some cases because without their permission I wouldn't do it. Actually, I've collected those papers and I now have the permission of everyone to republish them under the real names and there will be some surprises.

Jonathan Ritchie

Oh, that would be very interesting. So, I'm interested that you made the decision then to tape some of the discussions.

Ted Wolfers

Well, because I've been, you know, that was when the first courses in Australia, well, certainly Sydney University on the sort of politics and development. There was a sort of muddled discussion about the politics of development, the development of a whole new area of comparative politics and the drama of decolonisation. And I suppose I was influenced [by] that [experience] I had, I'm trying to remember, there's a book, I may be getting the dates wrong. There was a book called, I think, something like Africa Speaks, which was a collection of early nationalist writings. I read a few other things, and I thought it's interesting. I certainly didn't know who was going to be what. Let's be quite clear about that. But the idea that this was the generation-- I can remember my teachers at university said to me, if you go there, add …, because it was-- what else was there going? There was no university, you know, you are going to be meeting amongst those, you'll be meeting the people who will be prominent when the country becomes independent. And independence, given the kind of education I had, just seemed to be an inevitable thing. It was going to happen. I must say there were periods between then and when independence occurred when I couldn't see when or how it was going to happen. But at that point, if you'd asked me, I was pretty confident that it was probably going to be between about 76 and 80. But there were periods where I couldn't see that happening. And why did I say that? The Australian government was working in those four-year blocks. There was a certain pattern globally if you thought independence was inevitable. That was just the way it was. There was no great insight. But there were certainly periods when I couldn't see how it was going to happen because things weren't moving in that direction.

Jonathan Ritchie

So you'd met Davidson, you'd met Jim Davidson when you went down to the ANU and can you recall, I mean you mentioned earlier how you were familiar with his work … or in his book and so on. Was it from then and also did you then take some of those ideas with you when you went to PNG?

Ted Wolfers

While I was there, again I was not particularly productive. I did write a manuscript, but again I was just burrowing around the archives and it was also a period when the first photocopiers come into Australia. I'd never seen one before, I think, and they used negatives. It was all very complicated, but they had journals there that I'd never seen before on race relations and so I was reading a lot of African stuff. Jim showed me, gave me a copy of his Samoa mo Samoa to read in a manuscript [editor note: Samoa mo Samoa: The Emergence of the Independent State of Western Samoa]. And I remember being intrigued by it. And I remember also saying to him that I wish there was more about him in it, about his role in things, which was not something he especially wanted to do. But it sounded quite unique, the idea of a homegrown constitution and so on. And it certainly influenced me enough that in 19... I knew nothing about the Pacific, I mean, let's go back a step, but in 1966, I think it was, when I did, was it '66, I think it was, when I went for my interview in Hawaii. I thought, I can't, you know, if I'm flying across the Pacific, I've got to go somewhere and learn something, so I must go to Samoa, they've got a homegrown constitution and so on, so I actually went there and just for a few days and the trouble was I think they had the worst cyclone they'd had for 30 something years while I was there the airports were closed I couldn't get out. I arrived three days late from my interviews so it wasn't a good start to one's professional career, but I did get copies of the constitution. I did bring some back to show my friends in Papua New Guinea because the idea of basing a constitution upon popular consultation and so on was very different from the model that was being followed at that stage of decolonisation. I'm not saying it's unique in the world, but it was very unusual. And it was unusual, given what one's expectations were by then, about the prospects for constitutional and democracy in nearly independent countries. It was unusual that, you know, Samoa seemed to be working a few years later. So I was certainly very impressed by it. I'm not sure if I understood all the issues properly, but I certainly was very impressed by it. And I mean, I also heard Jim, I'm pretty sure I heard Jim lecture in Moresby on this at the community centre in Hohola later on. So these were ideas that some of us were aware of and were different from what was going on in many other parts of the world.

Jonathan Ritchie

And so your time at ADCOL was, you know, this was common currency. People were talking about independence coming within the next short decade.

Ted Wolfers

Well, nobody other than a small number of us. Most, many Australians, I could remember at one point, it was just after they'd introduced local pay rates, separate, what do they call it, a separate part of the public service for Papua New Guineans, and economic rentals, and there was a lot of agitation about all this among students. I frankly didn't know what they were talking about. I was a new boy. I remember I rang, it was the finance department it was called in those days, and spoke to some guy there and said, “Look, my students are talking about this stuff, and it's obviously a good amount of agitation. Could I have a copy of the relevant regulations or whatever it is that will explain to me?”. I really meant public documents. And the guy I spoke to said to me, “you'd better come and see me. You're some kind of a communist or something.” Which wasn't what I was, but you know, you weren't even supposed to be interested. And there were certainly a lot of people who didn't think independence was anything like coming.

There was also, I had a few experiences with people who obviously assumed my motives were quite different. Why else would you stay in the student quarters with Papua New Guinan? So I certainly got the hand on the knee treatment from one or two people who assumed that I had untoward motives. I'd never had that before. I mean, I was very innocent. I knew really very little about colonial society, and I wasn't trying to prove anything. I was just staying in the students' quarters because it was cheap, and I had nowhere else to stay. I didn't know anybody else. But there were also, I mean, there were people like the Rumans [expatriate family] who had really good relations with people there. I think it was Bill Carter, who was the Secretary for Post and Telegraph. He used to come out there at a weekend and swim in the pool and mix with the students and there was no issue. But for a lot of people, it was still a time when if you're walking along the street with a group of Papua New Guineans, expatriates driving past might stop and offer you a lift, not the Papua New Guineans you were with. There were places where Papua New Guineans knew they were. By then it was not legal to prevent people going into hotels and so on, but they were certainly drinking separately and kept separately, and I was, I guess, partly through growing conviction, but partly through innocence, I just became part of a Papua New Guinea network and in those days the guys were on their own. Nobody had their wives with them and their families where they were married I think from memory there was only one female student and she didn't live on campus so we networked, and people, I suppose in a way that I didn't fully understand at the time, Papua New Guineans students were all calling each other “bro” and they called me “bro”, and well here we are, 40 years later, and it actually means something that kids call me “uncle”. There was, we were, I wouldn't want to overstate the kinship thing, but it was more than just being contemporaries in the same place. And many have become, many, but not all, have become lifelong friendships. We don't walk past each other. We don't necessarily seek each other out all the time. But there was, it had a very particular meaning, because it was a very isolated, six miles, in the middle. There was nothing out there. If we wanted to go and have a drink on a Friday night, we had to walk, or walk partly on principle, and partly saved money, we'd walk to Boroka Hotel for a drink. So it was pretty isolated, there wasn't a lot of passing traffic, people dropping in, and there wasn't a lot of social life. So it was a fairly intense interaction amongst, I guess it was, I don't know the numbers anymore, it was probably 30 or 40 people.

Jonathan Ritchie

So that was, you were there for the first... class, the first year of ADCOL's operation, or was it the second year?

Ted Wolfers

I think, well, it started life a few years before that as the Public Service Institute.

Jonathan Ritchie

Oh, yes, sure.

Ted Wolfers

And then it became ADCOL, and I think it was the first or second year in the very early days, anyway. Right, yes.

Jonathan Ritchie

Okay. So, you mentioned the Public Service Pay case and the issues.

Ted Wolfers

That was before the case. The case came later.

Jonathan Ritchie

Later, yes. Okay. But was that the time of the famous Bully Beef Club?

Ted Wolfers

I believe so.

Jonathan Ritchie

Right.

Yet behind the glowing reports, students were restless. The SRC became more than just a debating body — it was a proving ground for political skills. Students used it to press grievances about food, pay, and housing, testing their ability to argue, persuade, and mobilise.

Michael Somare on Education, Public Service, and the Beginnings of Pangu

Source: Audio courtesy of PNG Speaks and the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery.

Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare inspired a generation. As a student and young leader, he helped turn friendship and debate into nationhood.

Image courtesy of the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, Australian National University (PMB Photo 47_24).

Description

Somare recalls how his career in teaching and the public service was shaped by early opportunities in the 1960s, including courses run by David Chenoweth at the Administrative College. Advancement through the ranks depended on qualifications such as the Queensland Intermediate and Leaving Certificates, which only a few Papua New Guineans had achieved. English fluency marked him out, enabling him to work alongside Australians and gain recognition. He describes how scholarships sent some peers abroad—while figures like Albert Maori Kiki attempted medical training before moving into politics. By 1965, Somare was part of discussions at the Papua New Guinea Society and at Kiki’s home that evolved into the formation of the Pangu Pati. He recalls enrolling in law and magistrates’ courses at the Administrative College but soon gravitating instead toward journalism and political organising, marking the beginning of his transformation from teacher and interpreter to nationalist leader.

Jonathan Ritchie

… It was later. Not in the first house.

Michael Somare

Not in the first house, but later on. That's right. It's similar.

Jonathan Ritchie

That's right.

Michael Somare

After the first house, second house, then when your dad was, yeah.

Jonathan Ritchie

And you had some of that. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Michael Somare

So that's how I got took interest in politics. Stuck by it, you know.

Jonathan Ritchie

Were you also aware of what was going on like in Africa? Because lots of new nations were being formed in the late 50s and early 60s.

Michael Somare

Yes, in that time that I asked to come back after doing my queen's and junior certificate up in Sogeri. David Chenoweth was conducting Institute of Public Administration, conducting courses for officers who want to qualify for the third division and the second division of Australian Public Service. So there were a group of us who were selected. You saw in the pictures, these were the group we were selected with to a little bit better ourselves in the education system.

Ian Kemish

This is at the Administration College.

Michael Somare

Yes.

Ian Kemish

Ah, I see.

Jonathan Ritchie

And this was also Sogeri, of course, where the group that Sir Mark [Oliphant] was referring to in 1962 did that. Yeah, Queensland.

Michael Somare

And this was said to.

Jonathan Ritchie

Allow, because up in, it's, I think the public service, until quite recently, if you didn't have, if you made school leaving, you can only go to the 4th division, which were lower paid.

Michael Somare

Yeah, the 4th auxiliary division.

Jonathan Ritchie

That's it.

Michael Somare

Most of us were in the 4th division, you see, 4th division of public service. Then later on, if you qualify in the 4th division, if you have an intermediate certificate or... Queensland Junior Certificate, you automatically go into the Third Division of Public Service. That's where most of us were, on the Third Division of Public Service.

Jonathan Ritchie

So you had that, but then, of course, what came along was this problem that you were all in the same condition and you should theoretically be equal with the Australians.

Michael Somare

Oh, yes, yes, yes, yes. That's true. No. I mean, I taught in Utu [High School in East Sepik Province], I had three Australian teachers and myself. Some of them are my very good friends, and we share our jokes and everything. I went to a remote place where all of us were Freinds because we were only English-speaking people. That's what I had with the rest of the house.

Jonathan Ritchie

So you were teaching in English though?

Michael Somare

Yeah, I was teaching English.

Jonathan Ritchie

At high school.

Michael Somare

No, intermediate school. It was Queensland Government under Paul Hasluck decided to bring in the concept of intermediate certificates, Queensland Junior Certificate. New South Wales was used in Sogeri, but first Queensland, and only a few of us were using Queensland curriculum. We were taught English and mathematics, two arms of mathematics, general mathematics and algebra and trigonometry. All these were in... So Level was, you know, for us at the time, it was it was something that we were heard. And later on they decided to bring in the matriculation. We have to matriculate. We in Queensland, we have to do senior. New South Wales, they introduced living certificate in Sogeri, you see. So kids used to sit for Australian exam. Curriculum is set in Australia and Sogeri kids. That's where Ebia [Olewale] and Russ [Soaba] came in.

Jonathan Ritchie

And then from places like Sogeri, then people would go into the public service, but either as teachers.

Michael Somare

Or maybe as medical... And there were scholarships offered to us, scholarships to go to medical school in Fiji. And quite a number of people... Yeah, Maori Kiki was a student. He was trying to become a native medical practitioner. But he failed, so he became a pathologist. He's a friend of mine. I can joke with him at any time.

Ian Kemish

How did you first meet him?

Michael Somare

Who?

Ian Kemish

Do you remember first meeting him at Maori Kiki?

Michael Somare

Yeah, in Port Moresby. That's when we will start talking about formation of Pangu Pati. And I used to come and stay with them. And once we got to know each other. Then we went back to Administration College. I enrolled for a matriculation year, but at the same time, I was doing a local...

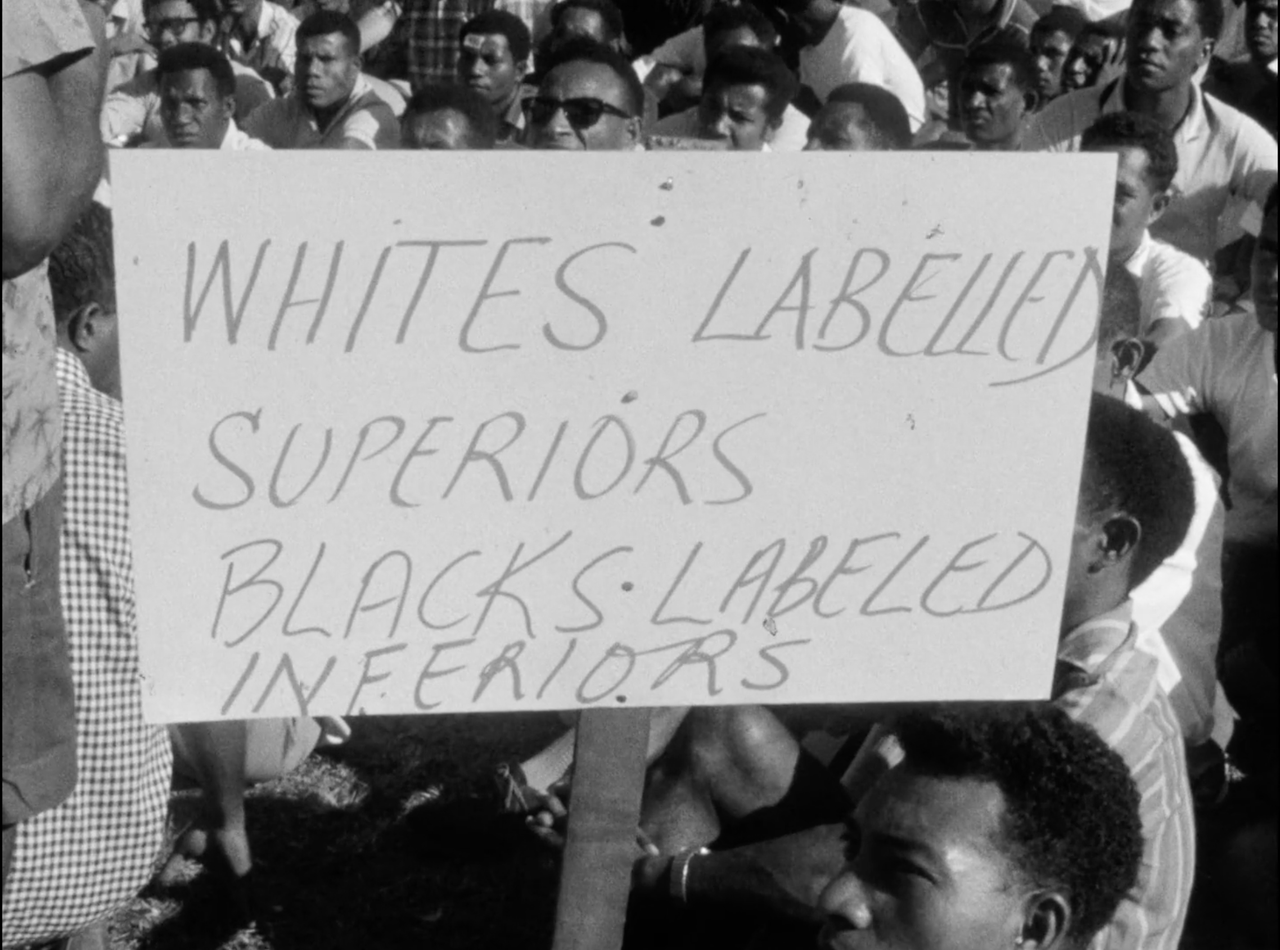

Everyday Injustice

The students’ politics were not abstract. They lived the inequality they protested. Joe Nombri, then president of the Tertiary Students Federation, was blunt in a 1969 interview:

“The difference in the salary … killed all the initiative in me … the person who’s doing the same work as I do gets more than three times as much.” — Joe Nombri

Joe Nombri on Unequal Pay

Source: Courtesy of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Archives. “New Guinea: Future Tense,” broadcast 24 September 1968.

Joseph Nombri was a fearless student leader from the Highlands who challenged inequality, helping turn classroom debates into the organised politics of independence.

Image courtesy of the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, Australian National University (PMB Photo 46_703).

Description

Nombri explained how unequal pay created resentment and racial tension: expatriates drove flashy cars while local officers struggled to survive. His words captured what every student at the Colleges knew: no matter how hard they worked, they would never be treated as equals in the colonial service.

Reporter

Indigenous public servants salaries are set at what it's considered the country can afford to pay and go on paying.

Meanwhile, expatriates are paid much more in the form of allowances that afford them a much higher standard of living.

This has angered the Tertiary Students Federation.

Its president is Joe Nombri.

Joe Nombri

Well, the difference in the salary made me feel well, I would say that it had killed all the initiative in me that, you know, I felt that I wouldn't do much more work than is necessary to get the pay I get because they person who's doing the same work as I do get more than three times as much as I get, and this makes me feel that this unjust has been done.

Reporter

Does this difference in pay scales cause very much racial tension?

Joe Nombri

It does, yes, I would say that because before that I didn't think any tension existed.

But at the moment they they may have been, but I was at school.

I would know, but now I see that there this a lot of tension between you see two blokes doing the same work but another bloke gets paid more.

The Australian bloke drives a flashy car around while the local officer has to work because it's not paid the same amount of money or comparatively same.

Brian Jinks on the Bully Beef Club, Networking, and Racial Barriers

Source: Courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Brian Jinks interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2008, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/12.

Description

Jinks reflects on the early networks that formed around the Administrative College at Six Mile in the mid-1960s, including what later came to be known as the Bully Beef Club. While he only heard of it second-hand, he recognises its importance as a space where Papua New Guineans like Michael Somare and Albert Maori Kiki forged connections outside the influence of expatriates. By contrast, most whites lived separate lives, with little real social interaction across the racial divide. Jinks recalls railing against the introduction of racially based salary scales in 1964, which entrenched inequality and made genuine mixing nearly impossible. Housing arrangements and pay differentials reinforced these barriers, even within institutions designed to prepare Papua New Guineans for leadership. His own efforts to host mixed gatherings exposed how rare and awkward such encounters were, underscoring the structural obstacles to equality on the eve of independence.

Brian Jinks

I can't. Senior Executive Program, that's right. “Septics”, what I used to call them. And I'm just going to drink water.

Jonathan Ritchie

Resuming interview with Brian Jinks.

Brian Jinks

We were mentioning about the administrative college and perhaps not on tape, the question of the Bully Beef Club at the administrative college came up. That was at the Old Six Mile, and it was before I went there, would have been about '64, '65, I ran across people like Michael Somare and Albert Maori Kiki and so on later on, but through, mainly through John Yocklunn, Sir, I beg your pardon, Sir John, Sir Yocklunn, I believe he's got two knighthoods, who was the librarian at the administrative college. And John came up, having been a student activist and so on at the ANU, and got right in with Pangu and Tony Voutas and so on. And John lived in the house across the road from us at Waigani. And so, and we used to, oh John and I used to go, John and I used to go down and have a few evening grogs at the Boroko Pub and places like that. And I think we were frowned upon by the Whites because it was full of Papua New Guineans in those days. But John and I used to get on very well. And he was great mates with Michael and so on, and they used to come out there for grogs and what all. So I used to, I mean it was only social as far as I was concerned, I never had much to do with it. But I don't know whether Michael would remember me now, but Andrew, our elder son, used to adore Michael because Michael used to play, you know, he used to play games with him and amuse him, but I thought he was very... marvel, do you know, have you met Michael? No. He is a marvelous guy, absolutely marvelous guy. Anyway, but yes, but the Bully Beef Club, you know, obviously was pretty important, but it's an example of the way things happened completely outside of the influence and knowledge of the whites and all that sort of stuff.

Apparently, from things I learned later on, the group, the early groups at the administrative college at Six Mile and then later early on when we moved out to Waigani, there were some quite important groups and networks and things formed there and discussions took place. And then for a time when the university was set up, university students lived in our dormitories at the administrative college and so on and so on. So there was a lot of early networking going on there. But you see, that was totally separate from the white community. We lived in our houses on the other side of the hill with our families and our children. It was a little bit like this. It was a little bit like the married guys on the outstations. You did your job during the day, you spoke to Papua New Guineans or whatever, but then the rest of the time you had very little to do with it. Now, one of the things about that, that I recall, and I railed against it, of course I was never in a position to have any influence, but in 1964 when we were at Finschhafen, they introduced the racial salary basis. You're aware of that? (Jon Ritchie: “Yes, yes”.) And I said at the time to the ADO and various other people around the place, and I wrote a letter to somebody, I don't know if it was the minister or the administrator or somebody or other, saying, “look, this is crazy. You need to have a situation such as been used in other colonies where you get a local living allowance and then you get paid a bonus, which is quarantined in your home country or whatever you do, so that the living conditions for the expatriates and the local people are more or less on the same level, and they can mix on a reasonable [basis]”. Of course, not that anybody wanted to do that, I suppose, but it was made almost impossible by the fact that Papua New Guineans were paid, what, half or less for the third of their salary for doing exactly the same job. I mean, it was absolutely appalling. And I mean, I can remember things like, for example, the house that we had in Waigani, for example. It was three bedrooms, it had an air-conditioned study, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. I think we paid $1.10 a week or something or another for it. But if you were a Papua New Guinea, you had to pay economic rental. I mean, it wasn't a lot. You know, a third of the salary and you had to pay for it. And then, so, there were all sorts of structural things against this, you know. And I can remember at the administrative college, I said, “Well, I can't”. I was more, I think, in the senior administrative program or senior executive program. I was involved in that early on, and then I was either thrown, I think I might have been thrown out or something, I don't think they wanted me anymore because I wasn't going along with the orthodoxy. But I remember in the early days of that having people up at our house, and we had the same problem, that you'd have the whites there, and they'd never spoken face to face to a Papua New Guinea, and in a social situation, they stood there, they sat there like stunned mullets. But I had people like Ted Dearer, Ted, and I can't think now, but all sorts of highly talented, charming, intelligent, well-educated. Oh, dear, dear.

Transcript

Sport, Culture, and Crossing Boundaries

Life at the Colleges was not all politics. Sport and culture also forged solidarity. John Kaputin was already a star athlete, having represented Papua New Guinea in rugby league at the 1962 Commonwealth Games.His interracial marriage to Australian lecturer Christine Lake challenged colonial norms and became a symbol of new possibilities.

Cultural events — from church gatherings to music and dance — gave students outlets beyond politics. More importantly, they brought together students from across the country: Chimbu, Gulf, Sepik, Milne Bay, and beyond. For many, this was the first time they had lived alongside peers from distant regions. It was here that regional identities began to give way to a shared sense of being “Papua New Guinean.”

Nanong Ahe, one of the Bully Beef members, later reflected:

“Young Papua New Guineans from diverse regions came together … to foster unity and advocate for independence.” — Nanong Ahe, oral history

Surveillance and Tension

The Administration was not blind to what was happening. Students recalled the Australian Special Branch monitoring their activities, trailing them to meetings, and occasionally offering them lifts — attempts to intimidate or recruit informants. Somare laughed about using the police as “free taxis,” but the pressure was real.[4] Some officials even suggested fencing off the Administrative College to keep it separate from university students, fearing that politics was spreading too quickly.[5] Such measures only confirmed what the students already suspected: their debates were dangerous to the colonial order.

Teachers as Mentors

The role of lecturers was crucial. While some Australians hoped to instil loyalty, others actively encouraged independent thought. Cecil Abel brought Christian moral philosophy into his teaching, framing independence as a matter of justice. Ted Wolfers ran evening seminars on constitutional development, exposing students to debates about political parties and home rule. Tos Barnett openly described the College as a political hothouse.

Their guidance was decisive. Instead of producing clerks, the College produced leaders.

“The students were not just preparing for administration — they were preparing for leadership. And leadership meant politics.” — Ted Wolfers

Ken McKinnon on the University, Debate, and Localisation

Source: Audio courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Kenneth McKinnon interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2008, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/16.

Description

Ken McKinnon was an Australian educator and administrator who helped shape higher education in Papua New Guinea, guiding the early development of the University of Papua New Guinea.

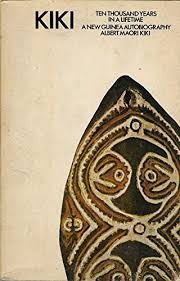

McKinnon highlights the transformative role of the University of Papua New Guinea in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Under Vice-Chancellor John Gunther and with professors such as Ken Inglis, the University fostered a new culture of open debate, drawing thinkers from around the world to the Waigani Seminar series. Students challenged visiting dignitaries, published literature such as Vincent Eri’s The Crocodile and Albert Maori Kiki’s Ten Thousand Years in a Lifetime, and gained confidence that Papua New Guineans could meet international standards. McKinnon contrasts this with the Administrative College, which had seeded early political networks but remained tied to public service orthodoxy. He also describes his own localisation programs, which gave thousands of Papua New Guineans leadership experience, culminating in a bold experiment where the top twenty administrative positions were quietly run by locals for a month. The result: independence felt increasingly possible, and expatriates—not Papua New Guineans—were the ones unsettled by the shift.

Kenneth McKinnon

And so that changed it straight overnight. People began to push on that. But in any case, one of the reasons I thought getting a degree was essential was I could see all everything the whole world over said this country's not going to be a colony for much longer, can't stand it. So we've really got to get moving. And so while all that was the pressure, the other pressure was on getting the country ready for independence in terms of training people to take responsibility, what we called our localisation course. And there's probably enough published that if you want to follow that up any time, the details of what we did, which was another set of lessons about things from my point of view. But I'll just divert for a minute and talk about the impact of the university.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes, yes.

Kenneth McKinnon

One of the great impacts on the whole of Papua New Guinea was the starting of the university. First, because you've got stellar people to be the chancellor and John Crawford and then Peter Carmel. Second, because you've got people like Oscar Spate and so on and Basil H… [editor note: likely to be Dr Basil (Stuart) Hetzel, the Australian nutrition researcher who led landmark iodine-deficiency work in the PNG Highlands in the 1960s and later headed CSIRO’s Division of Human Nutrition] . Basil, I've forgotten exactly how you say his name, but anyway, a CSIRO nutritionist who's tops, really tops, and various others to be on the council. And then a half a dozen to a dozen good professors signed up to be the first professors, Ken Inglis, for example. Ken is the most eloquent, very nice man. And they gave the drive to the university in the first period with Gunther as the Vice Chancellor, who did things at a pace and with impact that nobody else could have achieved in New Guinea. And that was his finest moment. But the upshot was a discourse in New Guinea that was totally different from everything that had gone before. before the discourse was handled by handouts from government and here was debate. And the Waigani series was established every about Easter. Brought people from all around the world, you know, freedom advocates and advocates for this or that other development of of the law saying, don't just take British law, think about French law and Japanese law and other law and ideas.

Jonathan Ritchie

Presidential systems.

Kenneth McKinnon

Yeah, all that had been yeasting in New Guinea for some years. And I remember Kerr coming when he was the Chief Justice of New South Wales and saying something that about independence and so on, and a young student getting up from the back saying, I don't know who you think you are, but we'll have our independence when we're ready for it, thank you very much. You white-haired... you know, stumbling old men who've got nothing to say about this that's helpful. It was helpful, but it was interesting input and a variety of people from around the world because Gunther was smart enough to put enough money into it to make it, you know, a really... I remember one great philosopher from Brazil, Freire, came and leading people from around the world, so the very best And from Australia. And so the idea that you could debate these things really got to go on there.

Jonathan Ritchie

So, because prior to the university, there'd been what, the administrative college or the administrative staff college, I think, and there was, otherwise there might have been a bit of opportunity through various organs of the administration, but here the university brought it all together, is that?

Kenneth McKinnon

The administrative college, David Chenoweth ran it, and it was, he was quite good. But it wasn't a university. It was public servants seconded out there under public service rules about debate. It did host the small rebellion clique, as it was at the start. And it gave good fostering to that because Chenoweth was, in fact, trying to make it an administrative college rather than an administrative training center. So it wasn't about routines and procedures and so on. It was about notions of government and ways of governing and so on. So it did have the makings of a tertiary institution approach. But this group emerged from there as the as the nucleus of the Panga Parti, and he got to go on with the university that just made free speech, just brilliantly receptive, you know, and endorsed that you could think rebelliously and all that kind of thing, so it was great. More than from the formal courses, I think, in lots of ways, in the first place.

Jonathan Ritchie

Thought of in establishing the university, that this would provide a forum for political debate and advancement of ideas, and obviously it's a university, but I'm just wondering whether people had thought that this was going to be part of the nation building exercise, not just in terms of producing doctors and engineers and lawyers, but actually producing people...

Kenneth McKinnon

A little bit, I think it was secondary to the professional, parent professional needs. But they were brilliantly lucky in getting John Gunther. And John Gunther, right from the start, he not only condoned that, he encouraged that kind of discussion. He made a staff room, staff bar and stuff that he patronised and was sort of joined everybody, most junior to most senior and perfectly willing to enter into debate and a good sense of humour, but a man's man in the best sense. I remember asking one young hothead student, whose name I can't bring to mind at the moment, they were, because it was very much a feature in Australia for student rights and things like that, they decided they'd have that. And this young man went and, because Gunther wouldn't give him what he wanted or could them, he went and laid down across the door of the Vice-Chancellor's office. So Gunther came back from whatever meeting he was and and said, You little ******* get out here and pick him up by the scruff of the neck and the back and throw him out. Well, it's not what Vice Chancellors should do, but...

Jonathan Ritchie

You haven't had that experience yourself.

Kenneth McKinnon

It's what... So I said to this fellow afterwards, I said, What do you think of John Gunther? Oh, he said, Tough ******* isn't he? he says, but I think he's actually quite good. I clearly respected him. But anyway, the whole atmosphere of the newspapers and the debate throughout the town became less colonial and more sophisticated in that sense. And many, many more Papua New Guineans entered into it. And that was a turning point in racial relations. And lots of people got the confidence to stand up and talk. And when the first graduates, a couple of them went to foreign universities and graduated with master's degrees, with no sweat, they said, Oh, we must be all right. And that's another big thing. And then people like John Waiko and others produced poetry and it was well accepted. And Uli Beyer came and I remember one of my people, Vincent Derry. Yes, yes. The reason he completed the book The Crocodile is that Uli Beyer says, these are your assignments. You won't graduate until you've completed this book. And again, Vincent …, who'd had a very, very bright fella but had a checkered career, he said to me, he said, Ah, ****** that I wish he'd just give an exam. And then he went, and another one who produced a book about that time was Albert Murray Kiki. Yes, yes. 10,000 Years in a Lifetime. And I was talking to Albert, who was on the Education Advisory Committee, and he was a wonderful, wicked sense of humor. And he laughed and joked about how we had bullied him into writing this thing and so on. And that and the support for artists like [Mathias] Kauage and [Timothy] Akis and a few others. And the soirees that went with art shows and chat and fun and the Institute of Papua New Guinea studies had various things, but then we were getting that moving too.

So there was a whole complete turnabout in the way, and the expectation of independence, of course, by then was really getting very close, and there was fear among Papua New Guineans who were really turning and saying, do you think we can do it? Oh, we couldn't do this, we couldn't do it. And there was a lot of reassurance and growth, and on our side, in the education, I turned over the deputy mainly to this kind of thing. And we decided that we would shuck off-- this is the Western District experience-- we'd shuck off every shackle that was holding us back. We wouldn't have any inhibitions about shucking off age, experience, seniority, gender, language group, anything, and we would get these people in. and we would turn the whole place upside down if necessary and give them the best coursework we could, not for any formal qualifications, and do that right through the country. And then when we'd done the first thousand, we'd picked, you know, 400 out of these. We'd give them more, and we would bring them back in and let them do a bit more work, and then pick 200 out of those, and then we'd put them in positions of first as learning positions, and then found out that that didn't actually teach anybody anything much. The only way you can learn to do an executive's job is to actually do it, because the issues involved in an executive's job are about judgment and stress and organising information, marshalling information into the lumps that can make, you know, what are the questions. And so we moved some up and some down and some around and gave them some experience. And then towards the end, for example, I took every senior officer out of their jobs and took myself out of the director's job without telling anybody. And the top 20 jobs were run by Papua New Guineans for a month without anybody knowing they're getting anything different. And the really interesting psychological piece of information out of that was the stress was on the white people for a change. And they couldn't understand it. Sitting in a room downstairs doing nothing all day with no authority was a huge learning experience for all of us. Anyway, we... then started to move people into more permanent positions and those that succeeded we went on with and those that didn't we left them where they were.

Jonathan Ritchie

So you would have...

Learning from Africa and the World

Students also looked beyond Papua New Guinea. Seminars introduced them to international independence movements. Memorabilia reprinted extracts from African student magazines like NSHILA, which warned that teachers often became the most dissatisfied branch of the service unless “Africanisation” policies were adopted.[6]

The visit of Tom Mboya, Kenya’s charismatic independence leader, was a revelation. Mboya spoke about responsibility and urgency in the decolonisation process. His message resonated deeply: “if Africans could achieve independence in the 1960s, why not Papua New Guinea?”.[7]

“Many of the laws for this country have followed closely those of Africa … the government policy must now change to one of Africanisation.” — Memorabilia, quoting African press[8]

Through conferences, visitors, and reprinted articles, students absorbed global lessons in how colonial peoples organised themselves, formed unions, and built political parties. They saw their own debates reflected in struggles thousands of kilometres away.

Tos Barnett Reflecting on Tom Mboya and Early Independence Debates

Source: Audio courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Tos Barnett interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2010, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/39.

Description

This interview segment captures the atmosphere of the early 1960s, when even mentioning independence in Papua New Guinea was seen as dangerous or “illegal.” Against this backdrop, visiting African leaders like Kenya’s Tom Mboya offered striking contrasts. Recalled here is a meeting in his Nairobi office, where his unionist background and uncompromising political style were on display. The story highlights how outside figures inspired reflection on colonial politics, and how PNG’s own debates about independence began to ferment in spaces like the Administrative College.

Tos Barnett

People were so vile and sort of sneaking along and waiting to be abused. Out in the highlands it was different, people stood very straight.

Jonathan Ritchie

Interesting, very interesting. I was going to ask you, Tom Mboya from Kenya had visited I think in 1964 and had come back and said, I can't believe these Papua New Guineans, they don't want to talk about government. But I guess, clearly the people you were with in Hohola, people like Oala Rarua and Murray Kiki, I guess, were they talking about independence?

Tos Barnett

Look, independence was, a lot of people thought it was illegal to talk about independence.

Jonathan Ritchie

Right. Well, it probably was. It was probably not illegal, but they were probably, yeah.

Tos Barnett

And I don't remember much discussion at that stage. A little bit later, yeah okay, but it wasn't really until the administrative college got going that they got together and it became a fermenting sort of pot of liberal independent thinking. Yes but I met Tom Mboya and he was Minister for something and I went to his office and, I think with Jenny, and we were interviewing him about the court system on the way and he got word that the union, and he was an ex-union, he came to politics through the union movement, and while we were in his office he got word that the union that organized the employees in the aviation industry were intending to go on strike and close the airport and he just raised his very large fist and thumped it down on the table and said “well, I'll nationalise the bastards”. I don't know what happened about that but it was a nice moment.

Michael Somare on the Bully Beef Club and the Power of Ideas

Source: Citation: Image courtesy of the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, Australian National University (PMB Photo 47_07).

Description

Somare recalls the informal gatherings at the Administrative College in the mid-1960s that became known as the Bully Beef Club. Students would pool their resources to buy tins of corned beef, sneaking food after curfew and using the occasion to talk politics, world affairs, and the future of Papua New Guinea. Influences included visiting figures such as Tom Mboya from Kenya and Filipino activists, as well as progressive Australian academics like Jim Davidson. Somare absorbed these ideas—he described how his friend Ebia Olewale literally carried Mboya’s book on freedom to absorb his wisdom—and how they all used this words to frame their thinking about independence. He also recognised the importance of communication, deliberately leveraging his role as a radio announcer to explain politics in Pidgin and build a following in East Sepik. For Somare, the blend of fellowship, debate, and media outreach made the Bully Beef gatherings a crucible for political consciousness and a stepping stone to national leadership.

Michael Somare

He's a friend of mine [Maori Kiki], I can joke with him at any time.

Ian Kemish

How did you first meet him? Do you remember first meeting up with Maori Kiki?

Michael Somare

Yeah, in Port Moresby. That's when we will start talking about formation of Pangu Pati. I used to come and stay with them and once we got to know each other, then we went back to Administrative College. I enrolled for matriculation here, but at the same time I was doing a local magistrate course and I didn't like that local magistrate so I decided to become a journalist too.

Ian Kemish

So this was 1965 I think.

Michael Somare

It's 1965, yes.

Ian Kemish

And where did you, you tended to meet in Hohola, right?

Michael Somare

Yes, in his place, through Papua New Guinea Society. The institute called Papua New Guinea Society. We used to have regular meetings in the hall, not very far from Maori Kiki's house. A number of us after talking, we would go back to his house on his veranda and we'd be talking. That's something interesting. Something interesting. And that's how discussions went. And we got to know each other. He was a clerk in the district office at Ela Beach. All stories about this one. And I experienced all that, you know. And we used to treat the Australian special branch services. I'd go in, a couple of my other friends. Albert is a senior man in our class. So we'd go, and because he was the senior man that was a married man, and we used to bludge in his house having coffee, the baby biscuit and, you know, so that's why I got to know Albert and I knew him very well. And then when I started talking about in '66, I started talking about, getting into politics, we have a Pangu Parti meetings that's where Pangu party was officially formed, in Hohola, at his house so quite a number of us. There was a medical officer, Dr. Taureka, all these guys were coming together and saying, we must get a movement going in the country. So that's how it happened.

Ian Kemish

This group getting together in Hohola, you called yourself the Bully Beef Club, is that right?

Michael Somare

Later on we became Bully Beef Club, but we were, Bully Beef Club name was given to, we were at the administrative staff college at Six Mile, and it was … why we call it Bully Beef Club, you know. Some people used to trade in, you know, at school materials and like a lap lap or a blanket or, and to get together, to afford a tin of corned beef. And that's how it all happened. And everybody get together after, Chenoweth would say that, yes, by time, 10 o'clock, everybody should be in bed. We sneak around looking for food and have bully beef, and that's how it all started.

Jonathan Ritchie

So in the famous Bully Beef Club before that, did you talk about, like I said, world events, or did you talk about some of the, you know, what was happening in America and the civil rights?

Michael Somare