In the early 1960s, Port Moresby was a city bursting at the seams. As the colonial administration expanded higher education, young Papua New Guineans poured into new training colleges — the Teachers’ College, the Medical College, the Posts and Telegraphs College, and the newly founded Administrative College. These institutions were meant to create a modern professional class. Instead, they exposed students to overcrowded dormitories, broken sanitation, and meagre rations.

An inspection in 1964 found that the Teachers’ College had jammed 192 students into accommodation built for just 112. Beds were lined up with “only inches separating them,” clothes and books piled on makeshift cupboards, and showers and toilets “completely inadequate” for the numbers. [1]

For many, these conditions revealed the contradictions of colonial rule: the same government that preached responsibility and leadership could not provide students with dignity or basic health.

“The number of beds … gives the impression of being a long sleeping platform instead of individual beds.” — Inspection report, 1964 [1]

Outbreaks of hepatitis swept through the staff, and cracked cement floors and broken sewerage lines were part of daily life.

Meanwhile, their education was meant to prepare them for “responsibility” in the colonial administration, yet their pay and status lagged far behind their expatriate counterparts. This gap between promise and reality was the seedbed of political frustration.

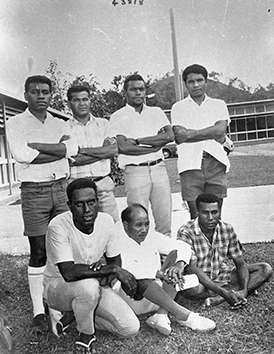

Image courtesy of Max Uechtritz

Frustrations Made Political

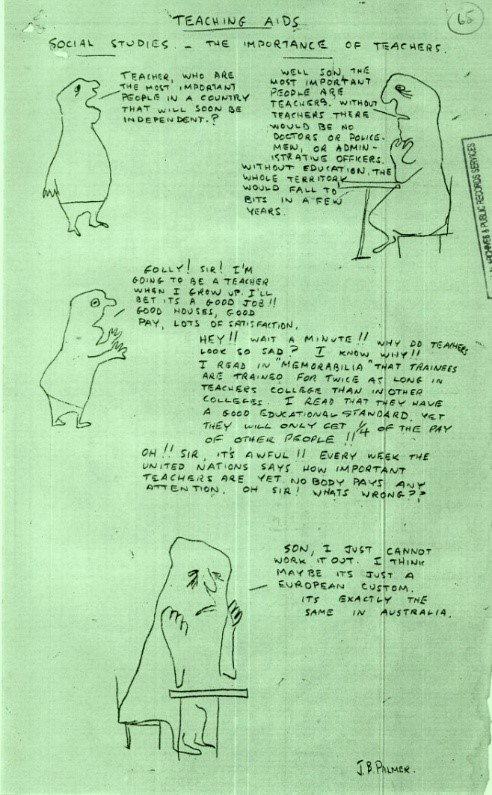

May 1964: An example of the political activity and fears of the student population from the Port Moresby Teachers’ College student magazine Memorabilia

The students themselves made the leap from frustration to politics. Memorabilia, the Teachers’ College magazine, became a forum for sharp critique. One editorial warned:

“Teachers are rapidly being put at a disadvantage … trained for twice as long … yet will only get a quarter of the pay of other people.” — Memorabilia, 1964[2]

Another contributor drew comparisons with African decolonisation, warning that Papua New Guinean teachers risked becoming “the most dissatisfied branch of the Public Service” if colonial inequities continued.[3]

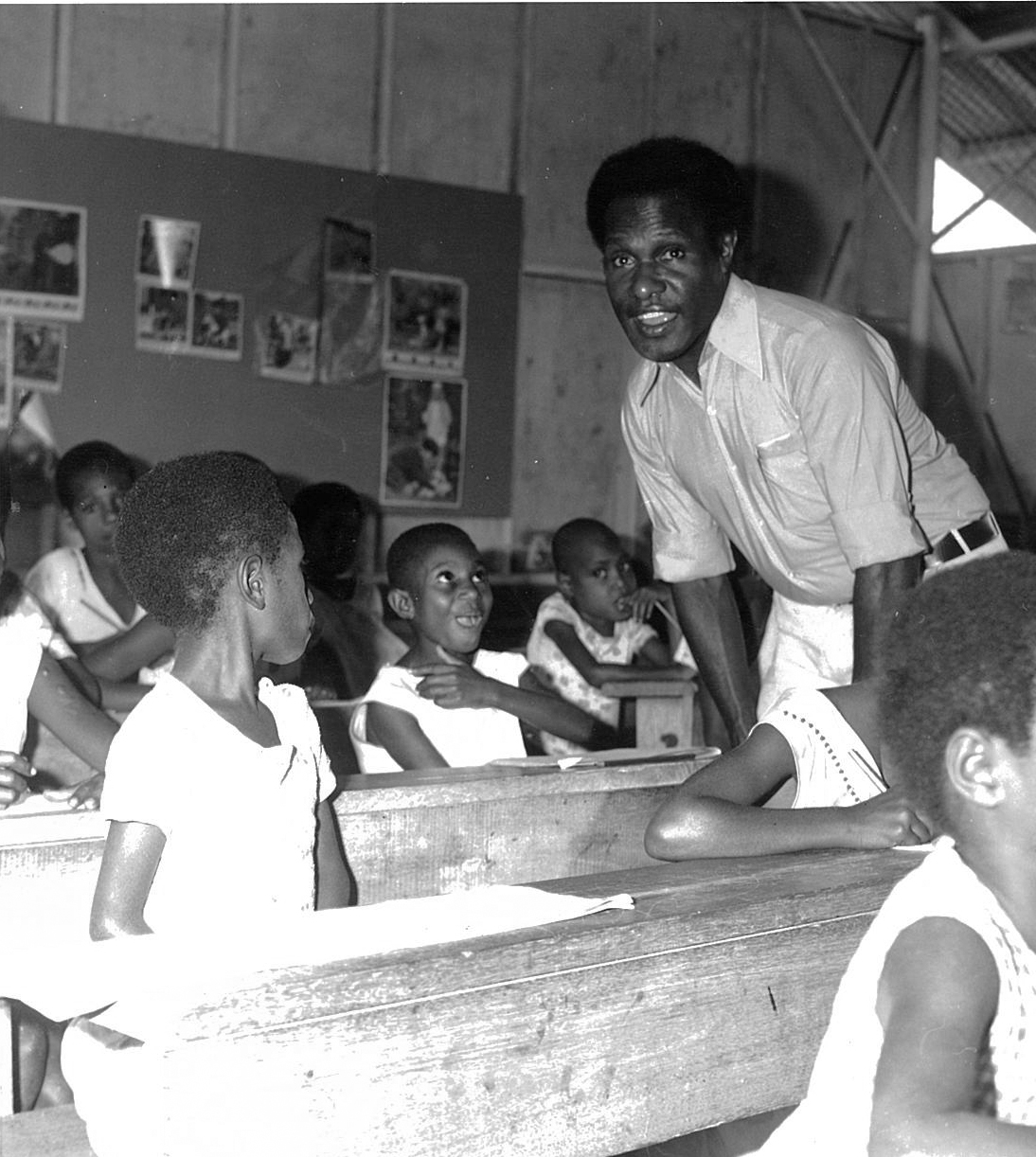

This sense of injustice fuelled the first stirrings of unionism. In 1964, students from across Port Moresby’s four colleges formed an interim committee to investigate establishing a Tertiary Students Federation (TSF). When the federation was inaugurated, Ebia Olewale became president and Joseph Nombri secretary. For the first time, student grievances were organised across institutions and expressed in nationalist terms.

Source: Photograph of Ebia Olewale teaching, courtesy of the Olewale family

Ted Wolfers’ Dramatic Arrival and Early Teaching at Adcol

Source: Courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Edward (Ted) Wolfers interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2009, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/33.

Description

Ted Wolfers was an Australian lecturer and scholar who guided young Papua New Guineans, linking education, justice, and the path to independence.

Wolfers recalls his bewildering first arrival in Papua New Guinea, which began with a car crash near Ela Beach and an impromptu welcome from a crowd of onlookers. Soon after, he joined the Administrative College under David Chenoweth, where he set about modernising legal teaching and experimenting with discussion-based classes. These sessions encouraged students—many of whom later became national leaders—to debate contemporary politics, decolonisation, and race relations, sometimes in multiple languages with interpreters. Wolfers also fostered early writing for the New Guinea Quarterly, helping young Papua New Guineans publish under pseudonyms to navigate colonial restrictions on public servants [5].

Ted Wolfers

… a very different route.

Jonathan Ritchie

Your original plans for the PhD, was that building on what you'd done with your Honors?

Ted Wolfers

Yes, it was to write, I think I'm correct in saying, it's a bit hard to remember, but I think I was going to write a sort of history post-war Australian colonial policy or something. And I certainly did a lot of reading and a lot of work on it, and I wrote a few papers at the time, which in some cases were mercifully not published. But I don't know if I had any overarching theory or that I'd done the in-depth work that was going to lead to a PhD. I mean, I'd read all the annual reports, I'd read parliamentary debates, I had read a lot. I had read a lot of government policy statements, but I never got to the point of... and I sort of sketched outlines, but I don't know that it was ever really going to become a PhD. It's hard to say.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yeah, and then of course your experience when you arrived in Port Moresby. Which, can I ask you about that? Can you recall the actual, you know, what happened? You presumably flew in, you saw the place, was it was disappointing, or were you happy, or can you recall?

Ted Wolfers

I can remember being bewildered if that happened, if that makes any sense, because we came in on a very, in those days the planes came in, I think it was about 5:30 in the morning, and so you came in over them, through these big clouds. I remember wondering if those were the highlands or if there were clouds, for example. I really knew very little. And then arriving at Port Moresby Airport, where they had this sort of mesh thing with Papua New Guinea and sort of watching, gazing through it as you arrived, which was a bit strange. And then I'm trying to remember exactly who met me. I think David Chenoweth met me. I think Sinaka Goava might have been with him, I'm trying to remember that. I was certainly met by a group of people and that's right, I had a very dramatic entry actually, you're reminding me because I was taken to Six Mile and I was introduced very early in the morning, I was introduced to a few people and then a driver came to get me to take me into town to see David Chenworth because in those days the sort of the office, if you like, for the ADCOL was in Konedobu, and a driver called Tobias, who subsequently became Sir Michael Somare's driver, was sent to get me, and he was a pigdin speaker, which I clearly wasn't. And driving into town at Ella Beach, near the sub-district office, as it then was, on the beachfront, an expatriate woman driver swerved across the front of our car and Tobias, to avoid her, swerved to his left we ended up hitting a tree. My introduction to Papua New Guinea was essentially a car smashed into a tree surrounded by several hundred Papua New Guineans who'd gathered very quickly to watch this and the only words I could understand that anybody was saying was bloody white missus and I remember the I think it must have been the Assistant District Commissioner, but anyway, some cop came out and asked me, was I alright? Where was I going? And I had to confess I had no idea where I was going. Going, because I just knew the driver was taking me somewhere, so it's a pretty dramatic entry to Papua New Guinea, I've forgotten about that.

Jonathan Ritchie

So you didn't ask the driver, his view?

Ted Wolfers

Oh, probably, but I'm not... I'm not sure that I want to catch any significance, so I honestly don't know. I can just remember that when he did come out and say to me, where are you going? I didn't know. I did know I was going to see David Chenoweth, and I said, you'd better ring David, and I think he found a way of doing that. And finding out where I was going, or maybe he asked the driver, I honestly don't know. But I'd never been to Port Moresby before, and I didn't know where I was, and I was probably a bit taken aback a bit in a state of shock having just collected a tree, and also, as I say in my introduction was all these people I'd never seen before saying things I didn't fully understand yes.

Jonathan Ritchie

So you went to see David Chenoweth and was it your understanding that you would be doing you'd be working at ADCOL?

Ted Wolfers

Yeah, well I think he said come up and stay there and you can do a bit of part-time teaching but there was a bit of a problem about the way they were being taught, let me just leave it at that and a desire to have somebody else do things. And so I ended up putting a lot more effort into it than I meant to and also I found that the textbooks being used, the curricula weren't what I would have thought was reasonably up to date by then so that was a bit of work. And then he encouraged me to do something which was probably pretty unusual, but pretty exciting too, which was to run I think it was one night a week we'd run a sort of just discussion class. All the students would gather and we would talk about a contemporary political issue. It wasn't formal teaching it was more sort of exploring the issues sort of thing and I had a rule, which was probably unusual, that you could use any language you like provided you provided an interpreter, because there was a linguistic divide amongst the students and those who spoke Motu and [those] who would get together and other pidgin speakers. Of course I didn't speak either language. So we used to hold these quite exciting classes talking about contemporary politics and the future of the country and decolonisation and so on. And I think I actually taped some of them but I doubt that the tapes have actually survived the ravages of the years. But it did mean that one was sitting- we used to sit on the floor around the tape recorder, I think, we did that a few times anyway- and you know, there in the group talking about the future of the country where people like Sir Michael [Somare] and so on, but they were just young men. One didn't know that they were going to be important one day. We used to argue about contemporary politics and it was very interesting and of course things like race relations were very important to people in those days. And because I was involved with the New Guinea Quarterly, I was also encouraging them, some of those guys, to write. And in those days, because they were public servants, they had to do so under other names, which they did. A number of them published. …

Everyday Racism

Featured in the May 1970 issue of Pacific Islands Monthly, the article But There’s No Urgency in Prejudiced New Guinea offers a timely critique of the colonial mindset that persisted in Papua New Guinea’s administration. Written around the time when local political movements were gaining traction, the piece examines entrenched prejudices and the slow pace of reform, even as student-led discussions—such as those of the Bully Beef Club—were building momentum toward independence. It presents a striking editorial perspective on why institutional attitudes were lagging behind grassroots aspirations.

Beyond the campus, students encountered daily reminders of inequality. Cinemas enforced segregated seating, buses separated passengers, and many shops refused to serve Papua New Guineans. Journalist Biga Lebasi, then a young reporter at the South Pacific Post, recalled:

“We were refused service in shops, barred from cinemas, or seated separately on buses … these everyday indignities drove a generation toward political awareness.” — Biga Lebasi

Christine Kaputin’s article “Economic Rents” in Pacific Islands Monthly (November 1966) gives us a rare glimpse into student life in Port Moresby during the 1960s. Writing from her own experiences, she described the daily frustrations of inequality — the unfair pay scales, the limits placed on Papua New Guinean students, the small indignities of colonial life. But she also remembered the energy of the times: the debates that ran long into the night, the friendships that cut across provinces, and the first sparks of nationalist thought. Her piece shows how ordinary moments — meals shared, lectures argued over, magazines passed around — fed directly into the political awakening that became the Bully Beef Club.

In a 1970 Pacific Islands Monthly interview, John Kaputin looked back on his student years with striking honesty. He recalled his time at the Administrative College, where he and his peers confronted the reality of racial inequality in pay and working conditions. For Kaputin, these experiences were not just frustrations — they were the fuel for a surge of student activism that reshaped his life. He spoke of how the energy of those years pushed him from the classroom into politics, setting him on the path to becoming one of Papua New Guinea’s national leaders. His reflections stand alongside Christine Kaputin’s 1966 article, giving us two powerful voices — husband and wife — remembering the same turbulent moment from different vantage points. Together, their accounts capture both the personal struggles and the collective awakening that gave birth to the Bully Beef generation.

Such experiences gave urgency to the dormitory debates. For young students, politics was not abstract. It was the indignity of waiting in one line while expatriates stood in another, the frustration of crowded hostels, and the sting of pay scales that valued their labour at a fraction of their colleagues’.

Biga Lebasi on Independence, Journalism, and the Bully Beef Club

Source: Audio and image courtesy of PNG Speaks and the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery.

Description

Lebasi recalls first encountering the idea of independence as a schoolboy in the early 1960s through letters to the editor and classroom debates. Influenced by writers such as Gaudi Mira, he began to think critically about self-reliance and responsibility, lessons reinforced in mission schooling where students were made to cook, clean, and manage on their own. At school he also heard of the newly formed Pangu Party and was tempted to join, drawn to the young nationalists who gathered in what became known as the Bully Beef Club. Ultimately, however, Lebasi chose journalism over party politics, recognising the need for independence in reporting. He admits the decision saved him from deeper disillusionment: frustration with colonial control sometimes pushed him toward violent thoughts, but journalism gave him an outlet to channel that energy into writing and critique. In hindsight, he believes his path helped preserve his integrity and allowed him to contribute to independence without losing himself to bitterness or violence [6].

Jonathan Ritchie

So when were you at Sogeri?

Biga Lebasi

1959 to 1960. I could be wrong.

Jonathan Ritchie

Sure. So you were at school when that first happened?

Biga Lebasi

Yeah.

Anne Dickson-Waiko

So when you heard about independence at Sogeri, was that just an idea that was being discussed? Or was the administration actually thinking about granting independence? Was there talk in the territories?

Biga Lebasi

There was a lot of talk through the papers with the letters of the editor, and I remember one particular reader called Gaudin Mirao, if you can remember that, from Kairaman, based here. And he was always writing to the press about his opinions about anything, education, health, which he was independent. And I was interested in what he was saying. In fact, I did reply to one of his letters to the editors in an essay English class on letter writing, on to write a business letter, letter to the editor, letter to mom and dad to make sure the difference. Like you say, “my dear mom, dear sir, your sincerely” and all that garbage. And independence, I thought about it. And I was grateful that I did go, we did go through quite all the mission that we were brought up in because there we were made to become independent. We get up, we clean our bed, go to have a wash… we all do our cooking and all that. We do our own little chores. We don't really have a mom and dad or auntie or uncle or grandparents, to do that job. So through that little process of education, how small it is, for something great, it's not to think, oh yeah, I am somebody, I am something. I'm going to stand up for myself, do things for myself. So when I heard about independence, I thought might do good, might bring something better, somehow to help me solve my racial issues.

Jonathan Ritchie

So I mean, in hindsight, people now think about the Bully Beef Club and the beginnings of the Pangu Parti. I think there was the select committee chaired by John Guise into constitutional development that began to perhaps bring these ideas into the mainstream. And I guess by this stage you were working at the South Pacific Post. Yes. So can you recall the first time you heard about any of those issues, the beginning of the Pangu Parti, for example?

Biga Lebasi

The Pangu Parti, when I first heard of the Pangu Parti, again at school. I thought about joining the party. I think I did, and later on, I never renewed my membership, because I don't think it was a good idea to join any particular party when you are generally supposed to be there in your reporting. But I really wanted to join them, to become part of what is called now the Bully Beef Club, because they were fighting for independence.

Jonathan Ritchie

But you felt it was not appropriate because you were a journalist, and you might be interviewing...

Biga Lebasi

Somarie or Ebia Olewale or the others. Yes. It wouldn't sound right, or I wouldn't be really honest in my report.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes.

Biga Lebasi

But I'm glad I didn't join that because I think I was becoming, I did say early on before the recording started that I became very bitter about the whole issue. And if I had a way, I would have taken a gun and go ****, like everything's happening right now. You mentioned, you know, all around the world, that's the sort of the end result of being so, you know, going through, so much hatred that you don't know how to deal with it. I think the answer is to declare my gun and go on a shooting spree. And I think I'm glad I joined the Post Courier and didn't and sort of mellowed through being involved with my work and never came to the stage where I had to use violence to find the answers that I was searching for. And I'm talking about my own personal career.

Jonathan Ritchie

Michael Somare has written at the time, under a pseudonym, about the “Secret Service Heaven-Feat”, I think it was the name of the title, where he was talking about the Australian Special Branch and how they had identified a number of people, Papua New Guineans, who were seen as potentially troublemaking or anything. Do you recall anything like that?

Ted Wolfers on Students, Pangu, and Early Political Alliances

Source: Courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Edward (Ted) Wolfers interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2009, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/33.

Description

Wolfers recalls tensions in the mid-1960s between students and national politicians. Many students were sceptical of their leaders’ literacy and independence credentials, and deeply frustrated by issues like local pay scales. Wolfers himself built friendships during this period with figures such as Barry Holloway and Tony Voutas, Australian expatriates who became close allies of emerging Papua New Guinean nationalists like Michael Somare and Albert Maori Kiki. He recounts Holloway’s unusual generosity in lending his battered car to students at ADCOL, symbolising trust and solidarity. While Wolfers was not directly involved in the formation of the Pangu Pati in 1967, he observed its emergence closely, recognising it as part of the global tide of decolonisation. Reflecting later, he notes that independence felt inevitable in principle but uncertain in timing, with crises in Bougainville and East New Britain eventually proving pivotal.

Ted Wolfers

… The case came later.

Jonathan Ritchie

Later, yes. Okay. But was that the time of the famous Bully Beef Club?

Ted Wolfers

I believe so.

Jonathan Ritchie

Right. Do you recall the Bully Beef Club happening? Did it happen?

Ted Wolfers

We... Look, there are different versions of whatever you say, somebody objects to it, but... people used to gather in the back room and eat together for example, and interact, and not everybody did. Some students went home so they weren't there. Some were. And then of course later I think they used to gather, which I wasn't part of, later on at Maori Kiki's house in Hohola and I think that's what is now called the Bully Beef Club. But did we meet at night? Did we eat food together or was Bully Beef around? Yeah. Was there in that sense of Bully Beef Club? Yeah, but was it quite the way it's understood now as sort of the formation of Pangu and so on? That was quite a bit later, and I suspect there's a bit of sort of reading back into history, if you like. Well, it makes a good story, doesn't it? Yes. It makes a good story, and it does give a bit of structure to a whole lot of interaction. I mean, it was a very small elite world at that time. One of the things David Chenoweth [ADCOL Principal] did was to send me out to see external university students at the University of Queensland because ADCOL, that was another reason I wasn't going to get my PhD done, ADCOL was looking after the external students who were, at least all the ones I ever met, were expatriates. patrol officers, co-ops officers, teachers and so on.

But it meant that firstly I used to go down to, you're bringing back memories now, I used to go down to Konedobu one night a week and run a small class, “Policy”, for the University of Queensland, a tutorial. And I also then went to see the external students and I went to where, I went to quite a few places in the Highlands and on the north coast and I also I went to the Gulf and that's where I learnt my exposure to rural life and I suppose the character of rural colonialism. The story I quite like telling was when I went to see an external university student at Moriavi [an old government station in the Gulf Province, near the Tauri River], the government station there. I had to go down the Tauri River and you had to go down on a mission boat. The mission boat wouldn't come back for me because there was a row between the mission and the airline that had brought me there, or charter operator, and so they had nothing to do with me. But I meant I couldn't get back up the Tauri. Oh, what is it? I can't remember. This is stupid. Sorry, it'll come to me. Anyway, it meant that I had to... the only way out was to walk and I had all these textbooks with me and stuff to teach political science and I was lucky that the co-ops officer, I think he was, at the station there was the father of a young woman who was the secretary of ADCOL at Six Miles and he found someone who would guide me out along the coast and we had to walk along the coast I think it was for a couple of days till we were able to get a boat which then took us into Karawa and I flew back from there so it was a bit of a …

Jonathan Ritchie

You were doing a patrol.

Ted Wolfers

Well I suppose I was without ever having intended to yes but that was my introduction to Papua New Guinea.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yeah, you were saying you were in the first just couple of months that you were staying in student accommodation, is that right? And then you moved out, or were you there for the...

Ted Wolfers

No, when I came back, I'm trying to remember, I came back just briefly in '66, I don't think so. In '67 when I first went up there, I stayed in the student accommodation for a short while, but I wasn't working for ADCOL when they were out at Waigani.

Jonathan Ritchie

Right.

Ted Wolfers

It's Tarabo... was the airport that I flew down from. Sorry, this is stupid.

Jonathan Ritchie

Oh, that's all right. Whoever's listening to this can look it up.

Ted Wolfers

It's stupid that I can't. It's part of my life. I can't. I've told the story so many times. I think I'm worried about the tape recorder. So I was only very, very briefly involved, really. But it was a critical time when there was a very small elite. And you just got to know lots of people very quickly, and they were connected with lots of other people. So that way you met the few Papua New Guinean doctors there were. Who was the president of the Tertiary Students' Federation? Ebia Olewale, who was a student at Teachers' College. On a Friday night, because there were very few women in that elite, there was not much you could do socially. They used to hold what were called “loose man dances”, where the guys would get up and dance to the music, I mean not holding hands, just dancing to the music.

Jonathan Ritchie

Western pop music.

Ted Wolfers

I think that's right, yeah, and you know having a few to drink, it just meant you got to know members of that elite in all sorts of ways in that very small world. I met some of the leading medicos, people who became big shots later on. And also, we did do a few things to connect up with political leaders because at that time there was a lot of tension between the students and the politicians. There was a lot of, you know, these guys are not educated, they know what they're doing. So we did a few things to bring them together, not always very successfully. And again, you see going to Parliament and sitting at the back of it, because I needed interpreters facilities, I was sitting actually in the press gallery at the back. So I could understand, you know, put on the headphones and it meant that in that small world you met all sorts of people, some of whom became lifelong friends.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes, yes, of course. So some of your students came and listened as well and watched that.

Ted Wolfers

Yes, I think I did take them in once or twice.

Jonathan Ritchie

Can you, you know, don't if you don't want to, but it'd be interesting to hear your views on who, you know, what the impressions you had of that first House of Assembly, I mean, who were the good performers, who were the people who perhaps weren't so good? Some of the issues perhaps from the expatriate members.

Ted Wolfers

Well, it appeared that first House to be very expatriate dominated. I mean, and [Ian] Downs sat where you would expect the Leader of the Opposition to sit. He would thunder on behalf of the people, he's a very powerful orator, and he would appear to dominate the house at times. John Guise was becoming an increasingly, well, he was already a visible and known public figure and, I think it was his nephew was a student at ACOL at that time, so I met Sir John. But you know you had the people who dominated the House were, if you like, in many cases not the kinds of people you would have expected to lead a country to independence. And then there were some of the Papua New Guinea members who were truly impressive but not always particularly well-educated. I mean, the member for Tari [Pari Rapua], I think he was, did not speak English pidgin or Motu. So he sat on the floor of the house with someone who would translate from pidgin or Motu into Huli and then he would speak Huli and it would have to be translated back if he spoke. He was the only one in that category but many of the other members were either non-literate or semi-literate but often very serious about learning and very inquisitive and very intelligent people. Some of them became very good friends over a period of time. And some were very well informed on particular issues. I mean, Wegra Kenu, who was from Vanimo, was concerned about the situation on the border with Indonesia, as well as he might be. So it was a very mixed bag of politicians. And there was a degree of interaction with the educated elite, if you like, so that you didn't meet. It was surprising how many people you'd met in what was a fairly small world, let me put it like that.

One of the first Papua New Guineans I ever met, in fact, that was even before I went up for David Chenoweth, was John Kaputin, because at Sydney University, I'm trying to remember who they were. … the very first, Henry ToRobert was there, Elias Vouvou, John, a couple of others, who, what's his name? John Tavur. Because I happened to be in the same college as Elias, and I was becoming interested in Papua New Guinea, I got to know him and I said, look, if any Papua New Guineans come through I might be interested in meeting them and learning something and one day some guy called John Tavur came through and he took him to meet me and I said, look he was a House of Assembly interpreter and I said, “do you think you could let me know what's a good time to come up and see what's going on in Papua New Guinea?”. And I suppose, surprisingly, given the sorts of questions I asked people, he sent me a letter saying I think this is a good time to come etc. So I went up there and I met him and I didn't know who he was and that he was already notorious for quite other things. And he invited me, we became friends, he invited me to his house, I went to his house, I met MPs in his house, but it wasn't planned, it was that sort of very small world. …

The Broader City Climate

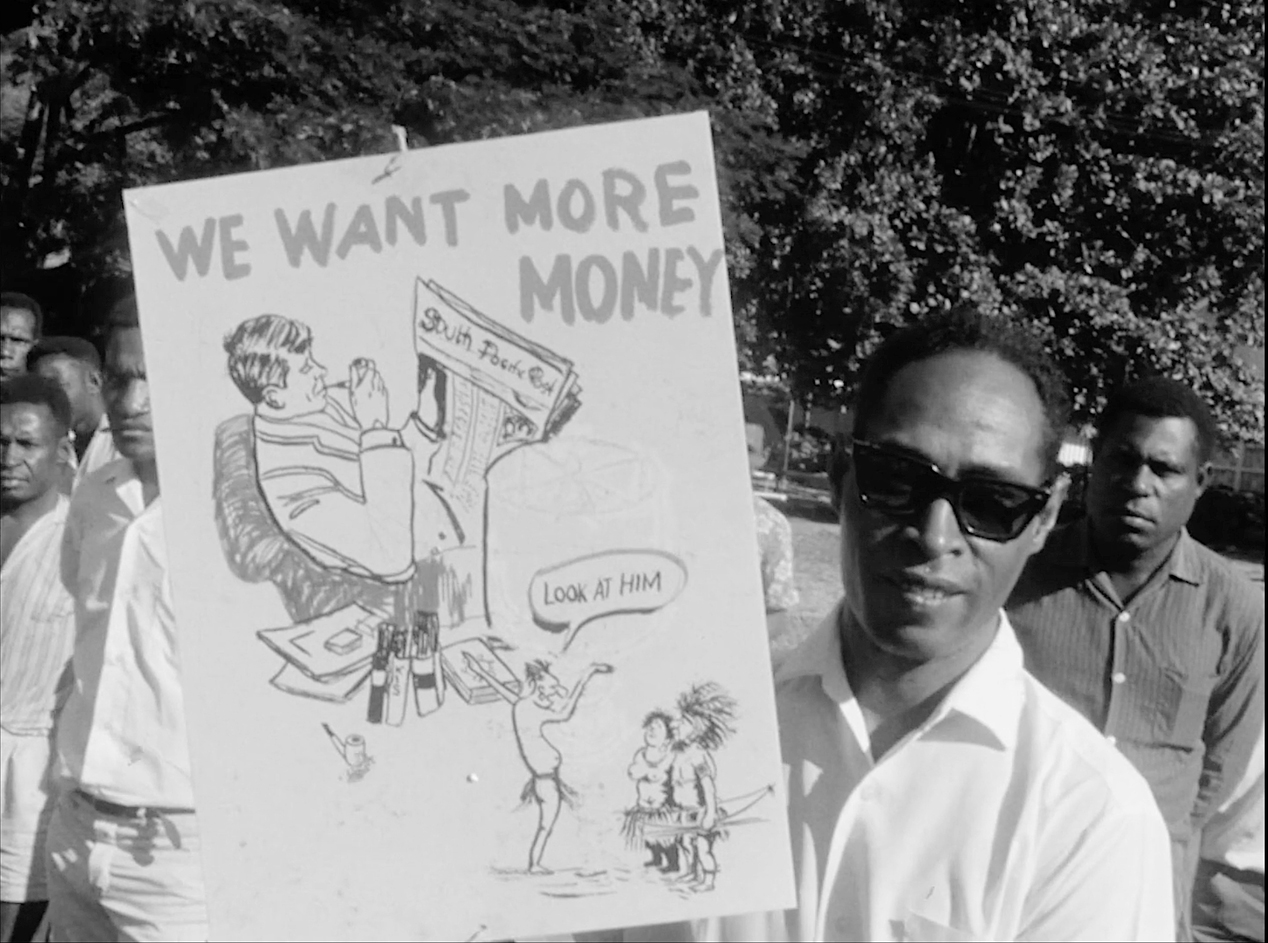

The inequalities that students faced were mirrored across Port Moresby’s workforce. The Port Moresby Workers’ Association, led later by Oala Oala-Rarua, pressed for equal pay for municipal workers. Teachers lobbied for a stronger federation to defend their rights. Pacific Islands Monthly captured the mood in 1968, warning of “a trade union war in Port Moresby” and accusing the bureaucracy of acting as though “people don’t always matter very much”

Oala Oala-Rarua speaks during a public demonstration in Port Moresby calling for wage justice and an end to racial discrimination, early 1960s. As one of Papua New Guinea’s first national leaders, Oala linked the struggles of workers and students to the broader movement for equality and self-government [7].

Student activism fed directly into these broader struggles. Delegations visited worksites, shared information about pay disputes, and invited labour leaders to speak at campus meetings. By the mid-1960s, students were no longer isolated; they were part of a city-wide movement demanding equality and recognition.

“Without the political education of the 1960s generation … the Bully Beef Club and the Pangu Pati would not have emerged.” — Patti Warn, journalist [8]

Charles Lepani on Decolonisation, Unions, and Political Awareness

Source: Audio and image courtesy of PNG Speaks and the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery.

Charles Lepani was a young economist-leader whose student-era ideals matured into diplomatic service and national planning [6].

Description

Lepani reflects on how his political consciousness was shaped both by education abroad and by union activism. Moving from colonial Papua New Guinea to high school in Queensland gave him what he calls an “educational decolonisation,” sharpening his sense of inequality and the need for change. This experience aligned him with the first generation of nationalist leaders, from Michael Somare to John Guise. His activism deepened when he won an ACTU scholarship—arranged with help from Bob Hawke, then a rising trade union advocate. Lepani trained in Australia with unionists such as Paul Munro and Rod Madgwick, immersed himself in anti-Vietnam War and Aboriginal rights protests, and nearly clashed with police during demonstrations in Sydney. He also took part in high-profile debates on independence, including a Four Corners program pitting Gough Whitlam against Territories Minister Charles Barnes. By the time he returned to Papua New Guinea, Lepani was not only politically aware but also armed with the organisational and advocacy skills that would shape his leadership in both the trade union movement and the independence struggle [6].

Charles Lepani

… take for the University of Papua New Guinea. And the awareness about independence began to grow. There was a distinct sense of colonialism, what it was doing to us when I was in Queensland. The contrast to coming from Papua New Guinea during colonial days and to go into high school in Queensland was such an educational decolonization process, as I always call it. And that was the basis of our sense of awareness of going forward for what it has become, at that time, quite a pretty well-grounded sense of political awareness by our first-generation political leaders, like now the Grand Chief, Sir Michael Somare, all the others. So John Guise, even my father was a member of Parliament then.

So yes, it was when I went to New South Wales, I spent two years in UPNG, got a scholarship from ACTU [Australian Council of Trade Unions], and the credit goes to Bob Hawke [future Prime Minister of Australia], who was then the president or industrial advocate for ACTU. And he came, we invited him to Papua New Guinea, Somare and Ruben Taurekas. Gavera Rea invited him to Papua New Guinea. They were the first group of activists, politicians, unionists, also to look at the public servants, Papua New Guinea public servants' equal pay case. And Bob Hawk did a great job. But he also had discussions with PSA, Public Service Association, executives then, great friends of mine, as they turned out, both lawyers, Paul Munro and Rod Madgwick [later became a Justice of the Supreme Court of New South Wales], who have now retired from the federal courts in New South Wales and won with the Arbitration Commission in Australia, Paul Munro [Australian industrial lawyer and judge]. And they decided to set up the scholarship for Papua New Guinea to be a unionist, trained unionist. And I was the first to win it. And I spent some time with Bob Hawke and his family at Sandringham at their home and got my early days of training as a unionist with the ACTU and public service associations. And Bob Carr, he was also involved in the New South Wales Trade Hall Council. I met him there and had some time with him. He could vaguely remember when he became the Minister of Foreign Affairs and a Senator recently.

But yes, so that's where I began to also get very politically active. In fact, I spend most of my time demonstrating Vietnam, against Vietnam War, and for Aboriginal causes in Australia, in Sydney, in George Street. Nearly got clobbered by the cops once in the streets of Sydney. But that's by the by. It's the awareness for Independence and I think ABC, Four Corners Program. It was a current affairs program that ran a debate between Charlie Barnes and Gough Whitlam, Honorable Gough Whitlam and Honorable Charlie Barnes.

Ian Kemish

So Charles was then the Minister for External Territories on Papua New Guinea

Charles Lepani

… independence. And I was invited to be part of that debate at New England University in Armadale. And I can recall there a very fiery young man talking about PNG's independence, talking about [setting] fire in Konedobu, the administrative headquarters of, at that time, your father, Jonathan, was around that time. So that was early beginnings of my awareness about independence and it moved on from there. When I went back through trade union activities, both for Public Service Association and private sector unions, I represented them in industrial advocacy cases. In fact, we won the first case for increasing of Port Moresby urban minimum wage before I chaired the national minimum wage board two years later to bring we in the in the Port Moresby in the minimum wage we increased the wage by $5 from $8.00 to …

Planting the Seeds of the Bully Beef Club

Amid this climate of grievance and activism, the networks that would become known as the Bully Beef Club began to form. Students met not only in classrooms and dormitories, but also in homes and informal gatherings. At night, students gathered at Albert Maori Kiki’s house in Hohola, where Elizabeth Kiki cooked for them. Michael Somare remembered arriving hungry, joking that Elizabeth would say, “What do you beggars want?” before serving food that fuelled all-night debates arguing about nationalism and justice.[9]

The Administrative College in particular was remembered as a crucible. Teachers like Ted Wolfers, Tos Barnett, and Cecil Abel actively encouraged political discussion, offering evening classes on independence and ethics. Wolfers later recalled:

“The students were not just preparing for administration — they were preparing for leadership. And leadership meant politics.” — Ted Wolfers

These informal gatherings — equal parts friendship, politics, and survival — coalesced into a community. Later, when they became known as the Bully Beef Club, they were remembered not for formal organisation, but for the intensity of their conversations and the solidarity of their friendships.

Sources:

[1] Papua New Guinea National Archives, ACC 18, Box 12028, “Strip Reports, 1961–1964.

[2] Papua New Guinea National Archives, ACC 429, Box 12358, “Memorabilia – Port Moresby Teachers’ College.”

[3] Papua New Guinea National Archives, ACC 429, Box 12358, “Memorabilia – Port Moresby Teachers’ College.”

[4] Photograph of Ebia Olewale teaching, courtesy of the Olewale family

[5] Courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Edward (Ted) Wolfers interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2009, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/33.

[6] Audio and image courtesy of PNG Speaks and the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery.

[7] Oala from MAX”: Image courtesy of Max Uechtritz

[8] Patti Warn, “Hindsight: A Workshop for Participants in the Decolonisation of Papua New Guinea,” University House, Australian National University, 3–4 November 2002

[9] Michael Somare SANA: From Sana: An Autobiography of Michael Somare (Port Moresby: Niugini Press, 1975).