By the mid-1960s, the students who met around tins of corned beef were no longer content to argue only among themselves. They had grown confident, disciplined, and impatient. Their grievances — crowded dormitories, unequal pay, everyday racism — were real, but they now framed them as political issues, not just personal struggles.

This was the turning point. The Bully Beef Club moved from being a circle of friends into an embryonic political movement. Its members began to test the colonial system itself.

“We thought, you know, with one voice you could be heard much more than as an ordinary individual.” — Michael Somare

An Oath of Secrecy and Solidarity

The students understood the risks. They were still employees of the colonial state — teachers, clerks, patrol officers in training. Openly challenging authority could mean dismissal or blacklisting.

As Michael Somare later recalled in his memoir Sana, the group swore an oath of secrecy. They pledged to protect one another, keep their debates private, and present a united voice when dealing with administrators or the Special Branch. For Somare, it was both a survival tactic and a declaration of seriousness.

“We promised ourselves that no one would betray the other … that we would stand together.” — Michael Somare, Sana

The oath gave the Bully Beef Club an identity beyond friendship. It bound them together in solidarity, a rehearsal for the discipline of party politics that would follow. It was not about espionage, but about trust. They promised to keep their debates private, to defend one another if targeted, and to present a united front when dealing with administrators. The oath was a shield against the colonial system — and a rehearsal for the discipline of party politics.

Somare later explained that secrecy was crucial. It allowed them to “speak as one” and to avoid being picked off as individuals. For young leaders, secrecy was both a survival tactic and a declaration of seriousness.

The First Confrontations

The Club’s first bold move was a deputation to the Public Service Commissioner. Outraged by discriminatory pay scales, they demanded an explanation in writing. For students, this was a daring act. It forced the Administration to acknowledge their grievances and revealed the determination of a new generation.

The deputation was part of a broader pattern. Students organised petitions, wrote letters to the editor in Memorabilia and the South Pacific Post, and pressed the Administration over food, housing, and sanitation. Each action chipped away at the fiction that young Papua New Guineans were passive recipients of colonial policy.

Meetings with Politicians

At the same time, the students sought out the wisdom of older leaders. John Guise, the first Speaker of the House of Assembly, spoke to them about parliamentary procedure and the art of persuasion. Barry Holloway, an Australian-born member of the House, explained the compromises and alliances required in politics.

For the students, these meetings were a revelation. They realised that politics was not just protest but also strategy: speeches, votes, committees, and the ability to work across factions. Somare later admitted that watching Guise in parliament convinced him that his own future lay in politics, not in journalism or administration.

Tos Barnett on Pangu Pati and Local Courts

Source: Audio courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Tos Barnett interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2010, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/39.

Description

Tos Barnett was an Australian lecturer who encouraged debate and critical thinking, inspiring his students to question colonial authority and imagine self-government.

This segment captures Barnett’s reflections on the late 1960s, when the Pangu Pati was emerging at the Administrative College. Several of its future leaders, including Michael Somare, Albert Maori Kiki, and Bill Warren, were his students. While his wife supported Pangu’s campaigning, Barnett’s own focus remained on establishing village-level courts. He believed that whatever political upheavals occurred in Port Moresby, communities would need a stable system of dispute settlement to endure change.

Transcript

Tos Barnett

… and what's the nature of the second relationship? And they were very difficult questions. But we found that they could be handled by pragmatically looking at the relationship against some sort of standard or principle. So what was the nature of Papua New Guinea customary law made?

Jonathan Ritchie

So by this stage, I guess we're talking about this is the mid to late 1960s now, that'd be about '67, '68, yes. And what was Port Moresby like at that time? We talked earlier about, was there a sense of excitement and impending change, I guess, by that stage?

Tos Barnett

Well, at this time, the Pangu Parti group were getting active at the ADCOL [Administrative College].

Jonathan Ritchie

And these were, of course, people who was... had you gone back to Hohola? No, you were actually living at ADCOL.

Tos Barnett

At that stage I was living in a house.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes.

Tos Barnett

So where did we get to that?

Jonathan Ritchie

I was just going to say the, you know, the people who were involved in the Pangu group, of course, were people like some of the people who you'd seen or you'd been friends with.

Tos Barnett

Well, Michael Somare was one of my students. Maori Kiki was one of my students. Bill Warren was one of my students. Look, I'm sure if you came up with a list of the new party early founders, they were all at the ADCOL, and most of them were in my classes, either in the senior management course, which was another thing which I hadn't spoken about, or the junior management course or the magistrates courses. And yeah, I wasn't personally much involved or interested in it. I knew that they were going through their growing pains and moving towards something, but I was totally involved in working at how you can create a court system which will continue on at village level, whatever, and turmoil might happen at central headquarters, and to the Supreme Court, because my experience was that in coups and revolutions major structures might fall but people still continue to live in the village. And if you can provide them with a way of continuing to run their own dispute settlements they'll be much better off than if it was total chaos. And I suppose that's what was motivating me, I was perfectly happy, in fact my wife, when the elections did come on, my wife drove the, what do you call, the people who man the election booths and hand out “how to vote cards” and things. Yes I know she drove them round in our minivan to put the Pangu Parti posters in and everything and “how to vote”. So we were certainly in favour of there being a change in the colonial system. But for me, my own attention was on getting the court system firmed up and down, down on the ground, I mean.

Jonathan Ritchie

And of course, what was going on, I guess, in a parallel development was that the university had started. And were they training lawyers at that first stage, or did that not come to later?

Tos Barnett

No, that came, I think it was Gerry Nash started the law faculty, and Peter Bayne was recruited there in '69. Yeah, in 1969, I transferred over to the university myself. In '68, I went down to Melbourne with the intention of doing a PhD on the custom of marriage and custody in the Motu-Koitabu people, which are the ones nearest. …

John Yocklunn on Joining Pangu and Coordinating the 1972 Campaign

Source: Audio courtesy of the National Library of Australia. John Yocklunn interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2008, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/20.

Description

John Yocklunn was an Australian educator who supported young Papua New Guineans, fostering confidence and leadership during the early years of self-government.

Yocklunn recounts how his path to Papua New Guinea was shaped by connections with Tony Voutas and David Chenoweth, leading him to join the Administrative College as Chief Librarian in 1967. Within weeks he was introduced to Albert Maori Kiki and became one of Pangu’s earliest members. He recalls Pangu’s modest beginnings: no parliamentary presence in 1967, only a few elected members in 1968, and an early decision to refuse ministerial posts to preserve unity. By 1972, however, Yocklunn was entrusted with coordinating the party’s national campaign, while Kiki stepped aside temporarily. The result was a breakthrough—around 25 seats—and Pangu’s central role in forming a National Coalition Government with Somare, Julius Chan, John Guise, and others, setting the stage for independence.

John Yocklunn

… remote, so I took a job in Canberra. So had I accepted at the time, I probably would have been one of the disaffected kiaps, or not kiaps, public servants, looking for the golden handshake. As it was, I didn't get there till '67. Now how I got there eventually was that in about '65, Tony Voutas was a patrol officer who was on leave. and went to ANU as a student. He was doing full-time Indonesian. So I came across him, and we used to have talks. At that time, I was in the National Library of Australia, working and going to ANU part-time. And I was involved in student politics at ANU. I was president of the students. In fact, in '65, and Ross Garnaut was my vice president in '65. Anyway, we got to know-- Voutas and I got to know each other. And he said, towards the end of his time there, about '66, he said to me, you should come to us to PNG and help me organize, because whoever is organized will get into power in PNG. So at that stage, he was interested in forming a political party based on local government councils. So in '66, he returned, I think, and he was elected in a by-election to the House of Assembly, the first House of Assembly. And then in June '67, Pangu was formed and he was a foundation member together with Cecil Abel, Barry Holloway and others. Then in about April of '67, I was visited in Canberra by David Chenworth, who was Principal of the Administrative College of PNG. He had probably heard of me from Voutas or also from Peter Biskup, who was a senior lecturer in history at the ADCOL. He had been teaching me librarianship at the National Library Training School, and prior to that I had known him and his first wife in university of WA. So, we went back. So, whoever told him about me, you come and offer me a job. So I thought about it, and in due course I applied and got the job. So, I came to PNG in 67, that's it. September '67 and started work as Chief Library of Chancellor of ADCOL Within a few weeks of Sir Murray, not Sir Murray, Voutas had returned from Lae and taken me to see Albert Maori Kiki, who was the full-time Secretary of Pangu. He was living in Hahola, and I joined up and from there I was a member, so I was one of the earliest members, though not a Foundation member.

Jonathan Ritchie

Because Pangu at this stage wasn't actually an entity in the House, was it?

John Yocklunn

No, it wasn't. It didn't have a presence and no presence in the House.

Jonathan Ritchie

That's right, yes.

John Yocklunn

However, at the elections for the second House of Assembly in '68, they did get several members in, including Somare. I don't think Barry Holloway got in in '68, but Voutas was a member in '68, he had to be re-elected. And so the few members of Pangu, there were several members, they decided that they wouldn't hold ministerial or assistant ministerial posts so as not to split the party. But there's one member, John Guise, who said, look, I've got to have a job because my people demand that I have an important job. So, Somare and others in the party supported him for speaker, so he was elected speaker, but the Pangu wanted to play a part of an opposition. So, come the seventy-two elections, Albert Maori Kiki wanted to contest them, so he resigned as, or not resigned, he left the position of... secretary temporarily, and I was told to look after the office and coordinate the national campaign. And David Stone writes about it in his book about the second elections. And in that election they won about 20 to 25 seats, depending on who you count. And with both the United Party and Pangu talked to PPP, tried to get the People's Progress Party, tried to get them to join up. So in the end, Somare announced that they'd form a national coalition government with Chan and with the Nationals. …

Self-Government as the First Step

The debates soon turned from grievances to visions of the future. Should Papua New Guinea push immediately for independence? Or first demand internal self-government?

Albert Maori Kiki urged patience, but also urgency:

“I don’t mind if independence does not come now … but internal self-government must come now, rather than having a target date of independence.” — Albert Maori Kiki

Kiki’s pragmatism showed how far the students had come. They were no longer just reacting to unfairness; they were beginning to map out the road to sovereignty.

Albert Maori Kiki on Internal Self-Government and Independence

Source: Courtesy of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Archives. “The Future of New Guinea,” broadcast 24 September 1968

[VIDEO HERE: Albert Maori Kiki on Internal Self-Government and Independence, ABC]

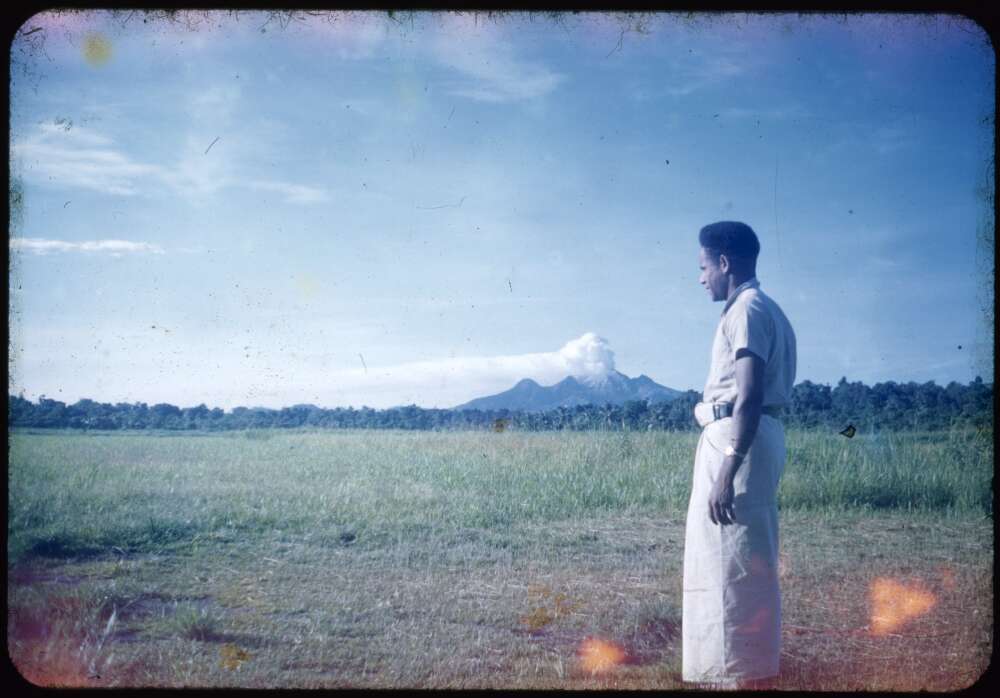

services with Mt. Lamington on the horizon, Popondetta, Papua New Guinea. Source: https://nla.gov.au:443/nla.obj-145187845

Description

At 36, patrol officer Albert Maori Kiki was already recognised as one of the Gulf District’s most politically active voices. Speaking just hours after an all-night meeting with other young leaders, he was cautious about declaring a target date for full independence. Instead, he emphasised the immediate need for internal self-government—the capacity to manage domestic affairs without direct Australian control—as the crucial first step. Kiki observed that most Papua New Guineans still wanted Australians present, and believed independence might be decades away, perhaps 20 or 30 years. Yet he insisted that learning to govern must begin at home: handling daily affairs, building institutions, and preparing for eventual sovereignty. His pragmatism balanced grassroots caution with a visionary insistence that independence would only come through active preparation and self-rule.

Reporter

A few hours before we spoke to him, he had just completed an all night meeting with a group of politically active young men.

The results, he said, would be important but they couldn't be announced as yet.

Maori Kiki is educated to matriculation level.

Would you like to see a target date set for independence?

Maori Kiki

Well, not not really, but I personally don't mind if not independent but internal self government come now rather than having the target date and say Papua New Guinea have independent now.

If you ask most people around in the country, we say we want Australians here, which means if you look at look around and see it independent in our mind is long way behind, perhaps another 20 years, another 30 years.

The Committee of Thirteen — The ‘Angry Young Men’

Out of this ferment emerged the Committee of Thirteen. Nicknamed the “Angry Young Men” by critics, the group was composed largely of former Bully Beef Club members and their allies. Their purpose was to present submissions on constitutional development to the House of Assembly.

Somare described their goal clearly:

“We are seeking home rule. We are not aiming for ultimate independence … we want to start the administrative machinery and from there make our way up to independence.” — Michael Somare

The Committee’s existence unsettled the Administration. Here was a group of young Papua New Guineans, still technically students and junior officers, taking constitutional questions into their own hands. It was an assertion of political agency — a statement that Papua New Guinea’s future would be decided not just in Canberra or Moresby, but by its own rising leaders.

Michael Somare and the Committee of Thirteen

Source: Courtesy of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Archives. “The Future of New Guinea,” broadcast 24 September 1968 (ABC_FutureOfNewGuinea_proxy_T440292).

[VIDEO HERE: Michael Somare and the Committee of Thirteen, ABC]

Description

At just 30 years old, Michael Somare was already at the heart of Papua New Guinea’s independence debates. Speaking as a journalist with the Administration Information Services, he described his role in the influential Committee of 13—a group sometimes called the “Angry Men.” While outsiders gave them names ranging from mocking to dismissive, Somare explained that their purpose was serious: to present submissions on constitutional development to the House of Assembly. At this stage, he was not demanding full independence outright, but advocating home rule—the creation of an indigenous administrative machinery that would allow Papua New Guineans to govern their own domestic affairs. From this foundation, he argued, the path to eventual independence would naturally follow. His words capture both the tactical caution and the quiet determination that would later define his leadership of the independence movement.

Reporter

Michael Somare, 30, is a New Guinean from the Sepik district, 30 years old.

He is married with two children and is educated to intermediate level.

He's a journalist with the Administration Information Services.

You're on a committee, the committee of 13.

What do they call you people out there?

Michael Somare

Well, we call ourselves Committee of 13.

We will call all sorts of names, angry men, oh, some rude names given to us.

But we believe we, we put our submit submission to the Select Committee in the constitutional development in the House of Assembly.

And it's up to the House and its members to decide whether they, what are they thinking in the terms that we are thinking.

Reporter

You are seeking what?

Michael Somare

We are seeking home rule.

We are not aiming for ultimate independence.

What we are trying to do is we want to start, we want to start the administrative machinery and from there we make our way up independence.

Responsibility, Not Just Slogans

Not every voice struck the same note. Oala Oala-Rarua, one of the most senior Papuan public servants of the time, insisted that independence must be matched by responsibility. In his words:

“Independence will mean … a great responsibility being passed from Australian hands into the Papua New Guineans.” — Oala Oala-Rarua

Oala’s caution reflected the tension within the movement. Some wanted independence immediately; others stressed preparation and capacity. But together, these voices — urgent, pragmatic, cautious — gave the movement depth.

Oala Oala-Rarua on Responsibility

Source: Courtesy of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Archives. “The Future of New Guinea,” broadcast 24 September 1968 (ABC_FutureOfNewGuinea_proxy_T440292).

[VIDEO HERE: Oala Oala-Rarua on Responsibility, ABC interview]

Description

By the mid-1960s, Oala Oala-Rarua had already emerged as one of Papua New Guinea’s most capable public servants and a likely future leader. A former teacher who had travelled widely overseas, he saw independence not simply as a political slogan but as a profound responsibility. In his words, independence meant “a great responsibility being passed from Australian hands into the Papua New Guineans.” His view captured both the optimism and the weight of expectation felt by the emerging nationalist generation—that self-government was not just about freedom, but about proving themselves capable of running the country’s affairs.

Reporter

It's here that Oala Oala Rarua, has his campaign headquarters.

Oala is a former teacher and is now one of the highest ranking Papuan public servants.

He's travelled widely throughout the world and is one of his country's obvious future leaders.

Have you found much interest in independence among the people you've spoken?

Oala Oala Rarua

Oh yes, very much, very much.

Reporter

What exactly does independence mean to you?

Oala Oala Rarua

I think independence will mean to, or well it will mean to me personally, means a great responsibility being passed from Australia’s hand into the Papuans and New Guineans.

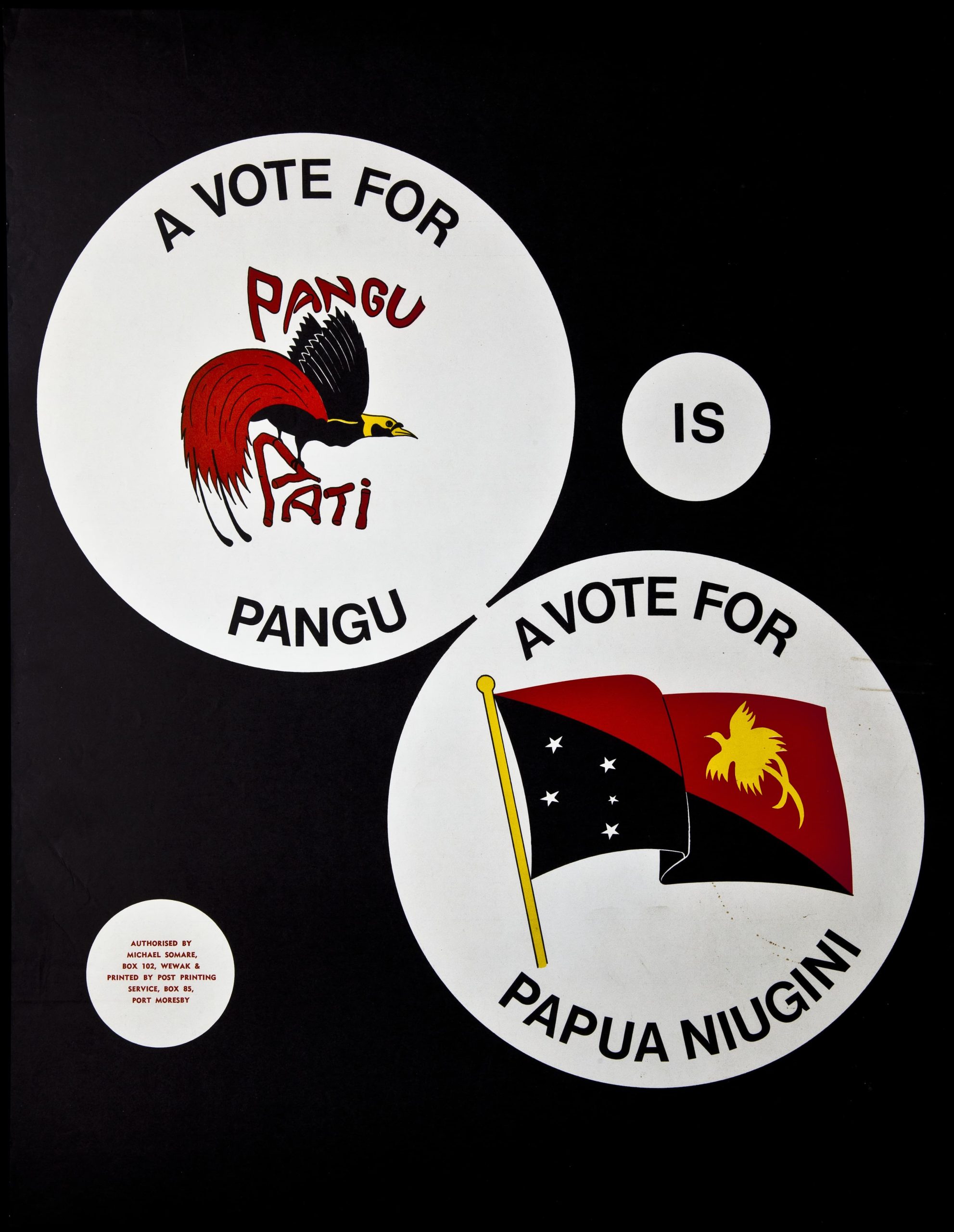

The Leap to Party Politics

By 1967, the Bully Beef generation had made its decisive leap. Their debates, petitions, and committees crystallised into the founding of the Pangu Pati. Pangu drew directly on the networks of trust built in the dormitories, in the SRC, in Hohola, and in the oath of secrecy.

Somare, Kiki, Rea, Nombri, and Olewale were central to its creation. Pangu gave structure to what had been informal, and gave national reach to what had been local. It was the bridge between the Bully Beef Club and the independent nation.

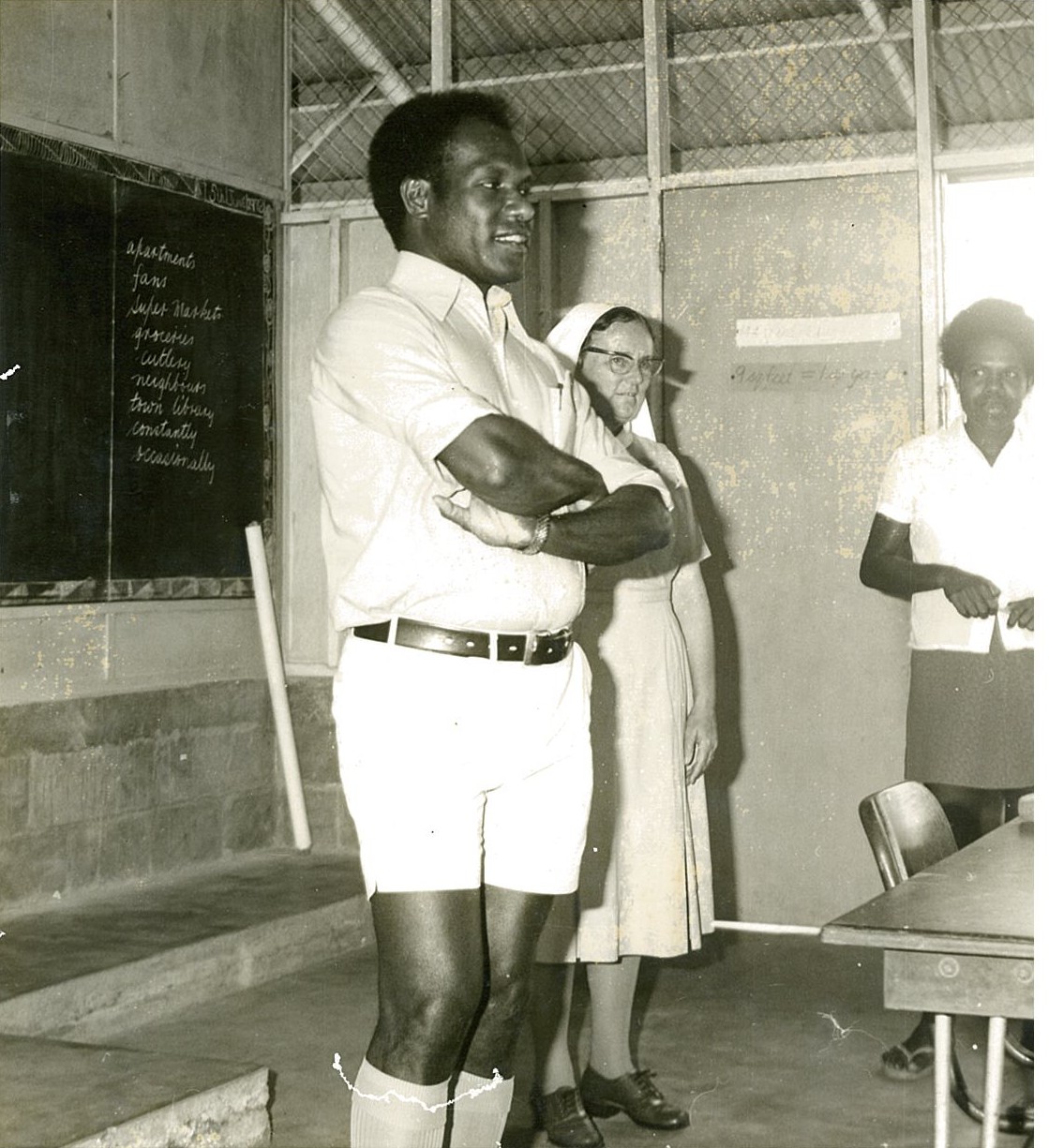

Ebia Olewale (above), student president and early leader, played a key role in the pay disputes, the Bully Beef Club, and the founding of Pangu. Source: Photograph of Ebia Olewale teaching, courtesy of the Olewale family.

Media Coverage and Public Perception

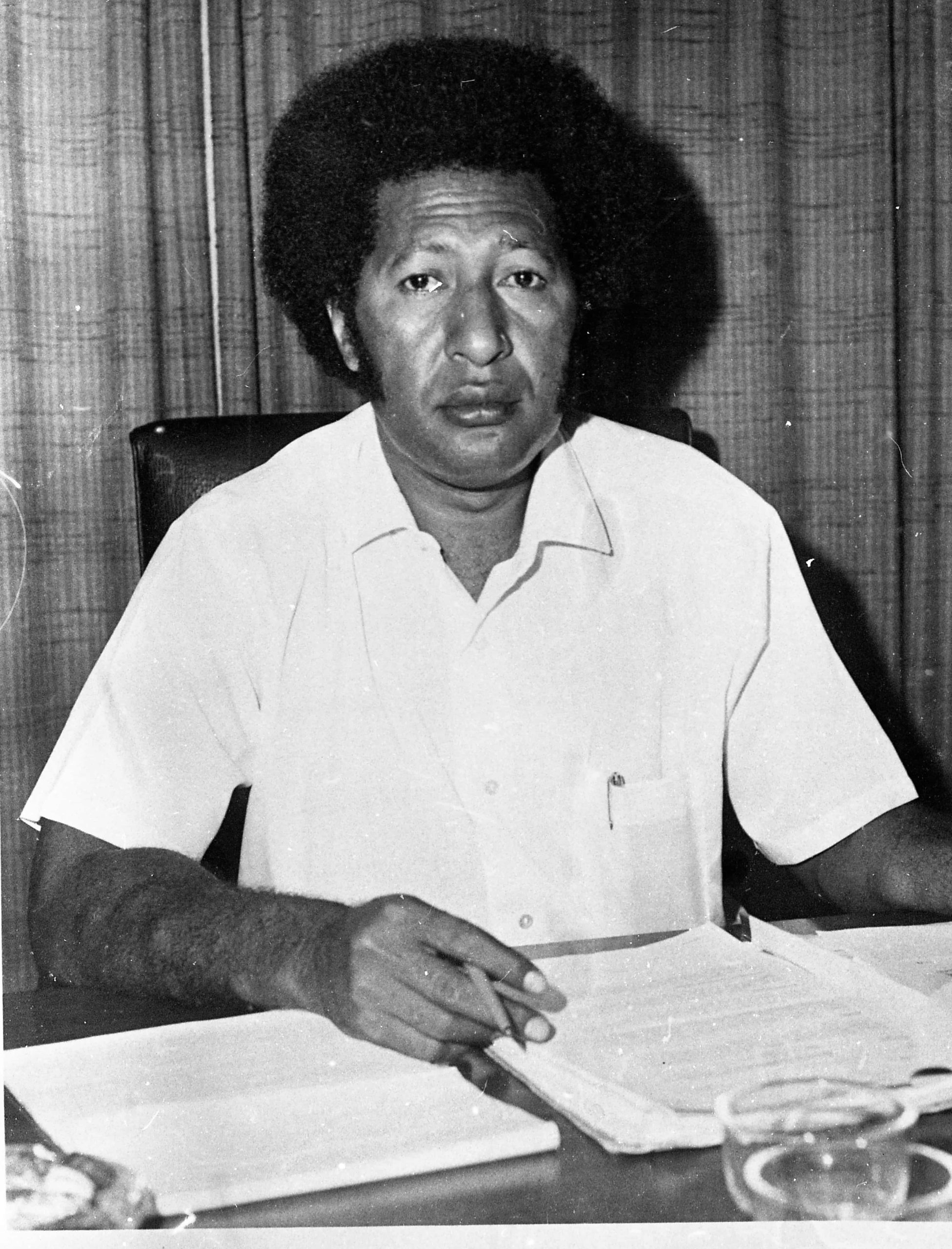

Philip Bouraga (above), a student at the Administrative College in Port Moresby during the 1960s. Bouraga was part of the generation of young Papua New Guineans preparing for leadership in the final years of Australian administration. He later became one of the country’s first senior public servants and diplomats, symbolising the transition from training to nation-building. Image courtesy of the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery.

Journalists began to notice. The South Pacific Post covered the rise of the “Angry Young Men,” while the Pacific Islands Monthly warned of radical students stirring trouble. The ABC put young leaders like Somare and Kiki on national broadcasts, amplifying their voices across the Territory.

For the first time, the public could hear directly from the Bully Beef generation. The Club was no longer a rumour whispered about by administrators. It had become a recognised political force, shaping debates about the country’s future.